This section details what you need to know about the NHMRC review of per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Australian drinking water.

Table of contents

NHMRC PFAS Review

From 2023 to 2025, NHMRC reviewed guidance on PFAS in drinking water as part of an update to the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines.

New and revised health-based guideline values and advice has been developed for the following PFAS to reduce health risks from exposure to these chemicals in Australian drinking water:

- PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid): 200 ng/L

- PFOS (perfluorooctane sulfonic acid): 8 ng/L

- PFHxS (perfluorohexane sulfonic acid): 30 ng/L

- PFBS (perfluorobutane sulfonic acid): 1000 ng/L

- GenX chemicals (hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid and its ammonium salt): no health-based guideline value can be derived at this time

The updated PFAS Fact Sheet is available to view in the Guidelines. The Guidelines are available for download, or in a digital format.

What are PFAS?

PFAS are a class of more than 4,000 manufactured chemicals that are not found naturally in the environment. These chemicals have been widely used in industrial and consumer products, such as firefighting foam, nonstick cookware, cosmetics, and waterproof clothing.

PFAS are sometimes called ‘forever chemicals’ because they do not break down easily in the environment and tend to build up over time in the bodies of living organisms. PFAS have been found in water sources globally, which has raised concerns about possible health risks from exposure of PFAS through drinking water.

How do PFAS get into drinking water?

PFAS can end up in drinking water supplies when products containing PFAS are used on land and washed into waterways and infiltrate groundwater, or when PFAS are used at home and are flushed down the drain.

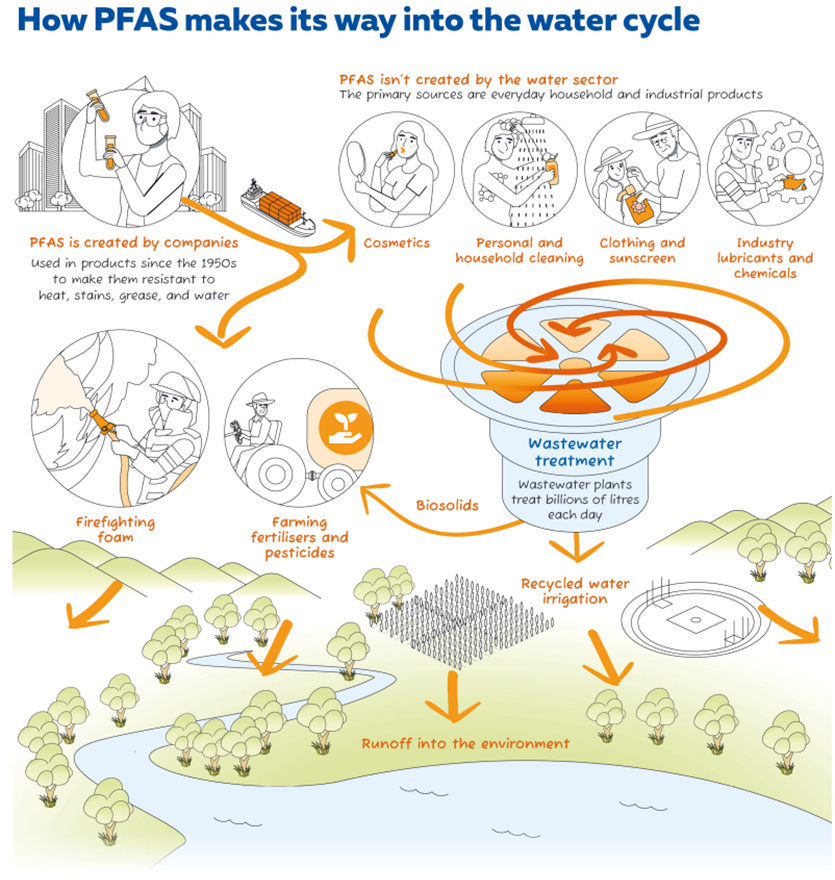

Figure 1, developed by the Water Services Association of Australia, shows some different ways that PFAS can move in the environment and enter the water cycle.

How much PFAS am I exposed to through drinking water?

Exposure to PFOS and PFOA from drinking water has been previously estimated to be approximately 2-3% of total PFAS exposure in areas with low levels of contamination. The vast majority of PFAS exposure, up to 90% in Australia, is believed to come from other sources, such as food and household products. This highlights the importance of taking a broader approach to manage health risks from PFAS exposure.

It is highly recommended and beneficial to reduce PFAS exposure as much as possible, and while there's a lot of focus on drinking water right now, it's crucial there is a cross-sector approach to managing PFAS contamination and exposure.

The enHealth Guidance Statement - Per-and polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) offers advice on reducing exposure to PFAS and the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing provides general information about PFAS, and potential health effects.

Health Effects of PFAS

PFAS exposure in humans has been associated with mildly elevated levels of cholesterol (confirmed by the 2021 Australian National University (ANU) PFAS Study), effects on kidney function and on the levels of some hormones. However, these effects are small and largely within ranges seen in the general population.

The NHMRC PFAS review concluded that the most critical health effects (endpoints) include potential carcinogenicity (ability to cause cancer) for PFOA, potential bone marrow effects for PFOS and potential thyroid effects for PFHxS and PFBS based on animal studies. These endpoints have been used to derive health-based guideline values. For more information see the Guideline development tab.

Monitoring of PFAS

A tailored, risk-based approach to monitoring PFAS and other chemicals in drinking water is recommended, as outlined in the Guidelines.

The key principle is to understand the water source used for drinking water, by assessing potential pollution sources and monitoring the raw water (before treatment), not just the treated water, to see if:

- catchment management measures are working

- new pollution sources have appeared

- system improvements are needed

Water suppliers should regularly share information with the community about current risks and water testing results, including for PFAS. This transparency helps to provide reassurance about the safety of our drinking water.

What happens next?

NHMRC is responsible for developing the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines, but implementation of the Guidelines, including monitoring or treatment, is outside NHMRC’s remit; it is the responsibility of each State and Territory. Water suppliers are not legally required to meet the new drinking water guidelines until the finalised guideline values published in the Guidelines are adopted by each State and Territory. Water suppliers will work with State and Territory drinking water regulators to manage drinking water quality using a preventative, risk-based approach.

Even though the new guideline values for PFAS are lower than before, there is no immediate health risk if you continue to drink tap water at the old guideline values.

Most water supplies are already below these new, lower values, which are designed to minimise risk from PFAS exposure. Very cautious assumptions were used to calculate the guideline values to ensure even the smallest potential risks are covered. Drinking water is just one of many ways you might be exposed to PFAS, so short-term higher levels in water are unlikely to increase health risks.

If monitoring tests show PFAS levels are above the guideline values, then the water supplier will manage the situation with the help of the State and Territory drinking water regulator. Some water suppliers might need extra treatment, which can sometimes take additional time and resources to plan and build.

If your water comes from a private bore, well, tank, or other unregulated source and you have concerns that your water supply might not be safe, it is a good idea to talk with your environment protection agency, local health authority or drinking water regulator. The responsibility for testing private drinking water supplies, such as rainwater tanks or private bores, lies with the owner of the property and it is up to them to test and ensure the safety of their own water supply.

You can also visit the Australian Government PFAS Advice page to find who to contact about the most current advice in your location.

What is the Australian Government doing to manage PFAS?

The Australian Government takes a precautionary approach to managing existing PFAS contamination. The government works to prevent or reduce environmental and human PFAS exposure wherever possible.

New evidence is considered to make sure policy and guidance supports positive health outcomes. This work includes: