Section 3 describes the approach taken in the Good institutional practice guide (the Guide) for implementing cultural change and Section 4 provides practical guidance.

Table of contents

3. Implementing cultural change

As institutions vary in size, maturity, resources and organisational structure, so too does the research culture within and between institutions. Many institutions already have processes and initiatives in place to support the conduct of high-quality research and to continually improve their research culture. This Guide has been designed to allow leaders to take a flexible approach to implementing the suggested activities to promote an open, honest, supportive and respectful institutional research culture.

It will depend upon an institution’s circumstances as to whether leaders choose to implement some or all of the suggested activities.

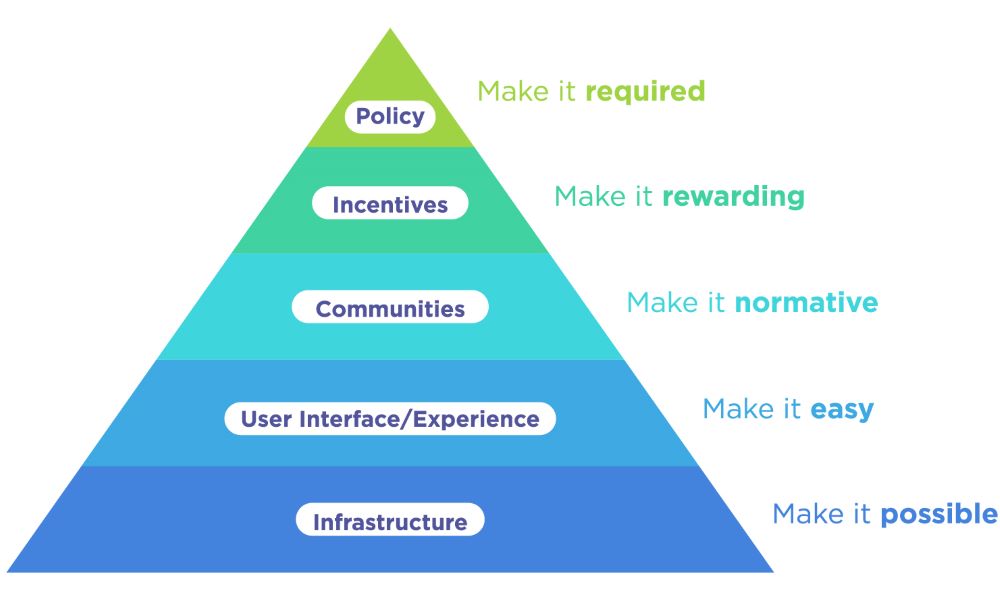

There are many and varied approaches that leaders can and do take to bring about cultural change. This Guide focuses on one of the available options – the ‘Strategy for culture and behaviour change’.1 The strategy describes five levels at which actions can be taken in a progressive manner, reflecting the fact that successful implementation of higher levels depends on successful implementation of lower levels (see Figure 1).

- Provision of basic infrastructure, including tools and skills, makes the desired change ‘possible’.

- Ensuring that this infrastructure is user-friendly makes it ‘easy’ for the research community to adopt the desired change.

- Once the desired change is recommended and accepted by (a large part of) the research community, its adoption may be considered ‘normative’.

- Incentives may be introduced to make adoption of the desired change ‘rewarding’.

- Implementation of the desired changes is made ‘required’ through the development and adoption of relevant institutional policies.1

By providing practical guidance in the form of suggested activities for each of the five levels of action, this Guide focuses on incremental, values-aligned changes that can be made within institutions. Embedding these changes is intended to foster a research culture in which researchers will feel supported to conduct high-quality research.

It is important to recognise that cultural change takes time and can be achieved with gradual improvements. It can involve a continuous process, implemented along different time frames for different elements of the research culture. Each element can be gradually and progressively improved through a continuous process of self-assessment, planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating.

3.1 Examples

Samples of graded implementation activities, based on those suggested in this Guide, are outlined in Table 2 and Table 3. An example of how the values outlined in Section 1 can be given practical expression by implementation of the suggested activities in this Guide is provided in Table 4.

| Intervention type | Activities: Leadership, supervision and mentorship |

|---|---|

| Make it possible | Identify training needs in research leadership, supervision and mentorship, to determine where efforts should be focused. |

| Make it easy | Ensure training in leadership, supervision and mentorship is open to a wide and diverse range of staff and held at times convenient to those with out-of-work responsibilities. |

| Make it normative | Make the qualities and characteristics of good leaders, supervisors and mentors a regular topic for discussion at meetings (for example, research group meetings, faculty meetings) and in communications from leaders. |

| Make it rewarding | Include evidence of supervision and mentorship skills as part of promotion and institutional award processes. |

| Make it required | Include requirements for training in leadership, supervision and mentorship in institutional policies. |

| Intervention type | Activities: Open science |

|---|---|

| Make it possible | Provide infrastructure for supporting open science, such as:

|

| Make it easy |

|

| Make it normative |

|

| Make it rewarding |

|

| Make it required |

|

Safe Working Environment

Institutions must create a culturally safe working environment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers to thrive and produce high-quality research.5

In such an environment, everyone understands and welcomes the cultural strengths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers and recognises that they are an asset to the institution. The working environment should be underpinned by collaboration and unity, rather than by competition which fragments teams: relationships should be valued.

Leaders can take the following actions to implement a working environment which is culturally secure and welcoming to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers:

- Develop a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) in collaboration with Reconciliation Australia to turn good intentions into real actions.6,7

- Provide a safe environment with overarching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ governance processes, safe and inclusive recruitment processes, and representation at executive and senior leadership levels.

- Establish Indigenous-led governance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ research.

- Allow Indigenous knowledge practices and non-Indigenous knowledge practices to complement each other.

- Establish and embed practices at the institution that demonstrate respect for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and observe cultural protocols throughout the year, not just during commemorative events (for example, by holding smoking ceremonies and by flying the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags).

- Foster collaboration among all researchers by holding workshops, seminars, masterclasses, and other less structured forums where people can interact and grow together.

- Prioritise and invest in cultural capability training for all staff.

When Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers feel welcome, appreciated and secure in the institutional environment, they will be more likely to thrive and produce high-quality research.

At the University of Glasgow, research culture is part of a multi-disciplinary team focused on creating a positive research culture by promoting collegiality, career development, research recognition, open research and research integrity.8 The objectives, activities and measures of progress are comprehensively described in their Institutional strategic priorities for research culture 2020–2025 plan.9 To date, they have:

- established a Research Culture Commons which people can join and contribute to cultural change and shared goals

- undertaken research culture surveys to understand where they are making progress and where there is still work to be done

- established annual awards to recognise and celebrate supervisors, principal investigators and research professional colleagues who contribute to a positive research environment

- created a Talent Lab with six diverse initiatives focusing on developing leadership in research and researchers as leaders.

The Stanford Program on Research Rigor and Reproducibility (SPORR), run by Stanford Medicine, has a variety of initiatives in place and others in the pipeline to support a culture of research rigor and reproducibility (R&R).10 Their initiatives are aimed at faculty, staff, graduate and postgraduate students and fellows, and include:

- core R&R courses such as ‘The practice of reproducible research’ and ‘Foundations of statistics and reproducible research’

- ReproducbiliTea, which is an international community of journal clubs that advance open science and improve academic research culture

- monthly R&R Grand Rounds; a consultation and feedback service on data sharing and data management plans

- free consultations for research teams writing training grants.

Early-career researchers can obtain help with study-design, analysis and interpretation from a network of like-minded experts across Stanford Medicine. It is intended that Stanford Medicine researchers and staff will be rewarded for their R&R accomplishments. They are also planning to incorporate R&R monitoring and accountability, incentives, and cultural change into the everyday research workflow.

4. Implementation

This section builds on the values outlined in Section 1. that support an open, honest, supportive and respectful research culture conducive to the conduct of high-quality research. It provides practical guidance in the form of suggested activities for each of the elements outlined in Section 2, to assist leaders to translate and embed the values into cultural norms within an institution and achieve continuous improvement. Sample self-reflection questions can be used by leaders as prompts to assess their institution’s research culture and determine their stage of implementation of cultural change. Case studies based on real-world examples, and hypothetical scenarios, outline examples of how some institutions have achieved positive change in their research culture.

4.1 Role modelling and leadership

Desired outcomes

Leaders model positive behaviours, attitudes, values and expectations, including caring for researchers and all research team members, encouraging collaboration, equity and sustainability of research career paths, and fostering and supporting the careers of research students and EMCRs.

4.1.1 Introduction

Traditionally, health and medical researchers are perceived as strong and successful leaders if they oversee a large team of staff, have many PhD students, and have a continuous flow of publications in high impact journals.

This guide seeks to reinforce a different version of what makes a good leader in research: one who promotes a vision for the future that is positive and values-based, and promotes reflection, collegiality and responsible research practices, including open science.

When a leader exemplifies and reinforces the institution’s core values, they help to create a culture that reflects these values and inspire staff to behave and act accordingly. A good research leader, with institutional support as appropriate:

- actively seeks to develop and broaden their team’s talent and skills

- recognises the contributions and achievements of all members of their team, including those from diverse backgrounds and disciplines

- values the team’s diverse outputs, impacts, practices and activities that maximise the quality and rigour of research

- creates a supportive and encouraging environment where everyone can speak freely about the team’s research activities and data, including its strengths and weaknesses

- effectively addresses concerns such as unhealthy competition, publication pressure, detrimental power imbalances and conflicts

- is honest and open about their decisions and mistakes

- practices humility and is open to alternative views

- ensures the equitable and transparent distribution of resources for which they are responsible

- reinforces an environment where ethical and responsible research practices are the norm including through regular discussions about improving research practices; taking effective, swift and positive action when questionable research practices first occur; and supporting those who identify and seek advice about potential questionable research practices

- models self-care and demonstrates that high-quality research does not need to be associated with excessive or burdensome workloads

- facilitates succession planning by supporting the development of leadership skills in research students and EMCRs.

When such attributes and behaviours are reflected in a team’s leadership, the research environment is more likely to foster a culture in which everyone feels supported and appreciated and strives to conduct high-quality research.

Supervision of early career researchers, Higher Degree by Research (HDR) candidates, undergraduate students and other research trainees plays a critical role in the responsible conduct of research and comes with many and varied responsibilities. The supervisory role incorporates oversight of all relevant stages of the research process from conceptualisation and planning through to dissemination of findings and as appropriate, publication and follow-up activities. Leaders should actively promote supervisory best practice, acknowledging and, as appropriate, rewarding genuine excellence in supervision.11 The Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research outlines that institutions have a responsibility to ensure supervisors of research trainees have the appropriate skills, qualifications and resources.12

It is the institution’s responsibility to provide ongoing training and education that promotes and supports responsible research conduct for all researchers and those in other relevant roles. This includes assisting researchers to develop their supervisory practice and follow their institution’s policies and other relevant disciplinary-specific policies.

A good supervisor, with institutional support as appropriate:

- serves as a role model to less experienced researchers

- maintains a high degree of professionalism and current knowledge of their field or discipline

- reflects on their own competence to provide advice and to seek objective feedback and support where necessary

- reflects the behaviours of good leadership

- initiates regular discussions about responsible research practices

- facilitates and supports access to ongoing learning opportunities

- creates a respectful research environment where scientific critique is encouraged

- acknowledges the work performed by others and recognises their contributions in a rigorous and fair manner, especially with respect to authorship of publications and on funding applications

- develops their own knowledge and skills in communication with, and management of, staff.

72% of respondents agreed that mentoring programs that address research quality and career development are amongst the most significant institutional interventions to improve research quality.

NHMRC sector survey13

A mentorship program can help facilitate a positive research culture for mentees by providing:

- encouragement and a second opinion

- assistance with managing their work pressures

- connections to relevant institutional and external support services and resources

- help to expand their networks of useful contacts

- ideas about what skills and achievements should be valued

- input and feedback on responsible research practices at all stages of the research cycle

- support regarding career opportunities.

4.1.2 Implementation

Implementation of better support systems for researchers (in particular, research students and EMCRs, and researchers experiencing difficulties such as vicarious trauma as a result of working on sensitive topics), encouragement of interdisciplinary collaboration and teamwork, and greater equity and sustainability of research career paths, will require a collaborative effort with institutions helping their staff to become better research leaders, supervisors and mentors. Suggestions for how leaders can help their staff to do this are provided in Table 5.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Peer Generative Power

Institutional leaders need to support and use peer generative power more strategically.

The unique strength of the power generated by cohorts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers from diverse backgrounds arises from their shared historical experience, co-understanding of problems with health and medical research and their shared aspirations to reform it. As a result, peer cohorts can have a much greater impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ health outcomes and on research capability strengthening. Such cohorts arise from informal networks, group facilitated research environments and university departments. They are led and driven by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers.

Peers can generate new research partnerships, shared identities, inspire and nurture upcoming generations of researchers, provide role models and support networks. Peer generative power emerges from peer structures and uniquely enriches the educational and research experience for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers. The outcomes include increased confidence as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health researcher, better decision-making, strengthened expertise, extended understanding of research and its potential impacts, and more. The strength of these peer cohorts should be recognised by institutions in policy and practice.14

4.1.3 Self-reflection questions

The following sample self-reflection questions could be used as prompts for leaders to determine their stage of implementation as outlined in Table 5.

Sample self-reflection questions:

- What level of funding, support and resources (for example, administrative support, material resources) is provided for training in leadership, supervision and mentorship?

- How many staff undergo training in leadership, supervision and mentorship and to what cohorts do they belong?

- How often are the qualities and characteristics of good leaders, supervisors and mentors discussed at meetings (for example, research group meetings, faculty meetings) and in communications from leaders?

- How does the institution reward staff who display exemplary leadership values and behaviours?

- How is the institution’s requirement that its leaders model positive behaviours, attitudes, values and expectations assessed and reflected in institutional policies?

- How does the institution provide a safe environment where issues about leaders/supervisors/mentors can be raised at an early stage?

- How are leaders supporting the use of peer generative power by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers?

- How are leaders supporting and investing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ research leadership?

4.1.4 Case studies and scenarios

It was after a team meeting where a postdoctoral fellow gave a presentation on research quality followed by a robust discussion, that the research team leader decided to hold a meeting with the other research leaders in the department to talk about how they could give research quality more focus. The result was the Research Quality Champions, a networking group in which early career researchers could discuss research quality and responsible research practices. The idea for the network was based on the model of Research Integrity Advisors, as required by the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research,12 and the University of Cambridge’s Data Champion program.15

A pilot for the Research Quality Champions network was actively supported by leaders. The Champions organised training, by internal and external experts, about research quality and responsible research practices. They now hold regular face-to-face meetings and have a virtual community space, to provide peer support and to exchange experiences and ideas. Not only does the network allow researchers to seek advice about research quality from researchers external to their own team, but the Champions also help their institution to continually develop and improve its processes related to research quality and research culture. Evaluation of this pilot clearly indicated its success, and it has been expanded across all departments in the institution. Furthermore, participation in the network is soon to be recognised by leaders in terms of workload and promotion criteria.

A team leader noticed that giving and receiving feedback during team meetings was becoming a little fraught as members were taking feedback as personal criticism and this was preventing what could have been constructive discussions about different ways of tackling problems from occurring. In response, the team leader engaged a facilitator to run a ‘giving and receiving feedback’ workshop with the team. Although some members were initially sceptical and saw it as an imposition on their time, they all participated, and it turned out to be a very worthwhile investment. The workshop gave the team a shared language and purpose around giving and receiving constructive feedback and having respectful conversations. The team felt valued, their communication skills improved, and much less time was spent diffusing tension and overcoming misunderstandings. In addition, the team leader noticed ideas were getting braver, which meant that projects were being taken in new and interesting directions.

4.2 Institutional resources

Desired outcomes

Leaders provide adequate support, or access to appropriate external support, for conducting high-quality research including expert and technical advice, methodological input and support, administrative support and material resources.

4.2.1 Introduction

An institution's commitment to, and the value it places on, the conduct of high-quality research can be demonstrated by the provision of expert and technical advice, administrative support and material resources for conducting high-quality research, to all relevant staff and students. This, in turn, can reinforce a positive research culture. Activities that facilitate the conduct of high-quality research, such as mentoring, education and training, the provision of rewards and recognition, and interdisciplinary research collaborations, require resource allocation.

4.2.2 Implementation

Leaders should aim to provide sufficient resources to facilitate the conduct of high-quality research and researchers’ use of responsible research practices. Suggestions for the graded implementation of institutional resources to support the conduct of high-quality research are provided in Table 6.

| Phase | Suggested activities |

|---|---|

| Make it possible |

|

Make it easy

|

|

| Make it normative |

|

| Make it rewarding |

|

| Make it required |

|

Communities of practice

Institutions are encouraged to share resources and infrastructure with each other by forming cross-institutional communities of practice to:

- discuss responsible research practices

- share resources for the design and provision of training in leadership, supervision and mentoring

- share resources for education and training of researchers in responsible research practices

- provide professional statistical support for all researchers

- share repository and data storage infrastructure for open access to research outputs and data

- discuss better ways to support individuals who report people for using questionable research practices

- implement and embed internationally recognised principles that promote responsible research assessment

- establish a formal feedback loop where institutions can share their experiences and challenges with implementing the Guide, possibly with a dedicated online platform, regular surveys and workshops.

4.2.3 Self-reflection questions

The following sample self-reflection questions could be used as prompts for leaders to determine their stage of implementation as outlined in Table 6.

Sample self-reflection questions:

- How have institutional policies and procedures been modified to support a positive research culture and responsible research practices?

- How do leaders encourage the use of infrastructure for supporting the conduct of high-quality research?

- How does the institution ensure that all researchers have access to support services as needed (for example, statistical advice, library services)?

- How does the institution ensure that its policies and procedures for resource allocation include consideration of the conduct of high-quality research?

- How does the institution recognise the value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ peer generative power for producing outcomes, processes and actions, which improve the quality of research practices?

- How are manuscripts reviewed prior to their submission for publication to ensure accurate reporting?

4.2.4 Case studies and scenarios

In response to publicity in 2019 indicating that only 17% of clinical trials at European universities had reported their results, Karolinksa Institute (KI) decided to address this issue at their own institution.17,18 By 2022, KI was reported to have uploaded the most results between December 2020 and November 2021 and received international praise from TranspariMED for their initiative. The following steps were important to the success of the initiative:

- Having the support of management who could ensure that resources were allocated for the long-term. Responsibility for the registration and reporting of clinical trials/studies was centralised to its existing research support unit and two additional full-time staff were hired for this unit.

- Making it easy for researchers to register their clinical trials. Staff developed a template containing the same mandatory fields as in the European clinical trials portal. Researchers were able to complete the template with trial results without having to learn how to navigate the portal. The support staff then easily and efficiently upload the results to the portal on behalf of the researchers.

- Developing an internal website with important and detailed information about registration and reporting of clinical trials so that researchers can easily find what needs to be done and how. The website includes a step-by-step guide for various trial registers and frequently asked questions.

- Providing specific support for researchers. The Chief Data Officer offers individual research support via email, as well as lectures and workshops, about what is required and how it is carried out.

- Joining networks of other researcher administrators working with registration and reporting. The Chief Data Officer found this to be a good way to make valuable contacts who could provide them with advice and tips.

Institutions can create formal roles in their senior management teams (an Academic Lead for Research Improvement or similar) with responsibility for, and supporting implementation of, activities to support the conduct of high-quality research. This approach is based on a key element of the UK Reproducibility Network (UKRN).

The UKRN was established as a peer-led organisation, with the aim of raising research quality and promoting initiatives that may help achieve this, as well as supporting a positive research culture. This includes the investigation of factors that contribute to robust research, promoting training activities and disseminating best practice, and working across local networks, institutions, and external stakeholders to ensure coordination of efforts across the sector. The key feature of reproducibility networks is their structure, which is flexible enough to allow for national, institutional, and disciplinary differences, while also enabling coordination of activity within and between these agents in the research ecosystem.19,20 Key features of the UKRN are:

- local networks - informal, self-organising groups of researchers and other staff at individual institutions, represented by a Local Network Lead

- institutions - universities that have formally joined the Network by creating a senior academic role focused on research improvement

- other sectoral organisations – organisations that have a stake in the quality of research (for example, funders, publishers, learned societies).

Institutions in Australia can consider joining and supporting the Australian Reproducibility Network, which has been recently established based on the UKRN.21

The Chair of an Australian Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) was struck by the apparent poor knowledge of biostatistics amongst those conducting research involving human participants. Following consultation with a senior manager in the institution, a qualified biostatistician was appointed as a member of the HREC. Initially, the biostatistician found problems with the biostatistics and protocol design in roughly one quarter of the research protocols in applications submitted to the HREC. Errors included simple ones such as being unable to replicate sample size, incorrect use of commercial statistical software and incorrect protocol design. The institution also supported a system of ‘biostatistician interns’ for the HREC - biostatistics students who had the chance to look at real world protocols as part of their studies.

Addressing these issues in consultation with the researchers led to improvements in research design and analysis, which are essential for the conduct of high-quality research. It also demonstrates respect for the participants in the research because well-designed research and appropriate analysis of the results is more likely to lead to useful outcomes.

4.3 Education and training about responsible research practices

Desired outcomes

- Leaders support and promote effective and continuing education and training of researchers about responsible research practices.

- Researchers have the knowledge and skills essential for the conduct of high-quality research.

- Leaders value time spent on education and training about responsible research practices.

4.3.1 Introduction

Researchers engage in ongoing development of their knowledge and skills throughout their careers. On the job training has traditionally been the pathway by which research students and researchers gain proficiency in research skills. Although many Australian institutions do provide training for their researchers about responsible research practices, it is internationally recognised that there is a need for greater consistency in the content and delivery of education and training programs for researchers and assessment of knowledge and skills attained.

72% of respondents indicated that provision of education, training and supervision was a key feature of the research environment that encouraged the production of high-quality research.

NHMRC sector survey13

Effective and continuing education and training about responsible research practices equips researchers with the necessary knowledge and skills to conduct high-quality research. It also ensures that researchers have a common understanding about the requirements and expectations for the conduct of research throughout their research career.

4.3.2 Implementation

Key considerations when developing or reviewing education and training programs for researchers include (but are not limited to):

- regular assessment and evaluation of the education and training needs of members of the institutional research community

- recognition that participation in education and training does not necessarily equate to attainment of knowledge or skills

- mechanisms for assessment of knowledge and skills attained by a suitably qualified assessor

- that the programs need to be accessible, suitable, flexible, practical, engaging, relevant and implementable

- how to meet the needs of individual researchers; for example, an experienced researcher (and recognition of prior learning) versus less experienced researcher/student

- the variety of routes to education and training in addition to formal lectures/tutorials and the traditional ‘master-apprentice’ model used for PhD training, with the attainment of some skills better suited to education via supervision

- the variety in the timing of delivery so that necessary knowledge and skills are maintained, and new ones are attained as required, during a researcher’s career

- provision of adequate support, resources and promotion of relevant programs

- regular assessment of the outcomes of the education programs with appropriate modification when required.

Suggestions for the graded implementation of education and training of researchers about responsible research practices are provided in Table 7.

| Phase | Suggested activities |

|---|---|

| Make it possible |

|

| Make it easy |

|

| Make it normative |

|

| Make it rewarding |

|

| Make it required |

|

4.3.3 Self-reflection questions

The following sample self-reflection questions could be used as prompts for leaders to determine their stage of implementation as outlined in Table 7.

Sample self-reflection questions:

- What kinds of support and resources are provided for all modes of delivery of education and training (for example, expert, technical and administrative support, infrastructure, material resources, list of recommended training/tools)?

- How are the different modes of delivery used to ensure that the training is accessible, suitable, practical, engaging, relevant, implementable and meets the individual’s needs?

- How does the institution encourage and facilitate peer support for education and training about responsible research practices?

- How does the institution recognise research groups that have high engagement rates in education and training?

- What requirements for education and training in responsible research practices are included in institutional policies?

- How does your institution measure and check attainment of relevant knowledge and skills?

4.3.4 Case studies and scenarios

With the support of senior management, the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute undertook an exercise to encourage preclinical researchers to improve the quality of their cardiac and metabolic animal studies.25 This involved provision of education and training to increase awareness of concerns which can arise from suboptimal experimental designs, and provide knowledge, tools, and templates to overcome bias.

Participants received a one-hour presentation that included questions and discussion on concerns regarding the quality of animal research, the ARRIVE Guidelines,26 types of bias, and practical examples for improving experimental design. They also attended a seminar on improving disease modelling and candidate drug evaluation and were provided with flowcharts and templates to encourage them to track and report exclusions of animals. Two short surveys were conducted over 12 months to monitor and encourage changed practices. The major findings included:

- a willingness of investigators to make changes when provided with knowledge and tools that were relatively simple to implement, for example, structured methods for randomisation, and de-identifying interventions/drugs

- resistance to change if this involved more personnel and time

- evidence that changes to long-term habits require time, follow-up, and incentives/ mandatory requirements.

Like in any profession, researchers are frequently faced with dilemmas: Can I exclude particular observations from my research? Can I use exactly the same data set for multiple papers? The Dilemma Game app has been developed by Erasmus University Rotterdam to stimulate awareness of, and an open and critical discussion about, integrity and professionalism in research.23

The game prompts participants to consider, choose and defend (and possibly reconsider) alternative courses of action regarding a realistic dilemma related to professionalism and integrity in research. The game consists of dilemmas with four possible courses of action which the players can choose from. It is important to note that due to the complexity of integrity-related dilemmas, there is no winning or losing in this game. Rather, by defending and discussing these choices in the context of a critical dialogue, the game aims to support researchers in further developing their moral compass. The game can be used in a variety of settings, and has three modes: Individual, Group, and Lecture.

For some years, the Dilemma Game was played as a card game. In 2020 the game was digitalised in order to reach a wider audience and inspire continuous attention to the topic of research integrity. Discussing research integrity is vital as it contributes to an open, safe, and inclusive research culture in which responsible research practices are deeply embedded.

4.4 Rewards and recognition

Desired outcomes

- Criteria for assessment of researchers (for example hiring, promotion, rewards and recognition) include the recognition of efforts that promote a positive research culture, and measures that recognise the diversity of research activities, practices and outputs that maximise the quality of research.

- Criteria and evaluation processes for assessment, rewards and recognition are transparent.

- Individuals and groups in administrative and support units who make positive contributions to an open, honest, supportive and respectful research culture are recognised and rewarded.

4.4.1 Introduction

There is a clear and growing international consensus for the need to reform researcher assessment practices to further support the quality of research and the attractiveness of research environments.27,28,29,30,31 The current assessment of researchers usually relies on a narrow set of quantitative journal and publication-based metrics such as the journal impact factor, article influence score and h-index as proxies for quality and impact. These assessment processes focus strongly on past performance thereby missing the opportunity to consider a researcher’s potential, promote quantity and speed at the expense of quality and rigour and promote individualism over collaboration. Furthermore, there is mounting evidence to show that assessment processes that rely on publication and journal-based metrics are prone to multiple biases and discrimination.26,28

44% of respondents felt that the features that had the most negative effect, and hence discouraged the production of high-quality research, were emphasis on publishing in top-tier journals and how researchers are assessed for promotion.

NHMRC sector survey13

A positive research culture is supported by assessment practices that recognise collaboration, openness, engagement with society, and the diversity of activities, outputs and outcomes that maximise the quality and impact of research, while providing opportunities for diverse talents.27

By rewarding and recognising activities and behaviours that support such a culture, leaders can play an important role in encouraging and reinforcing those activities and behaviours, which ultimately contribute to the conduct of high-quality research.

Assessment practices that contribute to a positive research culture also include the recognition of researchers’ workloads that are beyond their formal roles or employment arrangements such as membership of committees, contributions to broader institutional and community activities and organising conferences. In addition, they include the recognition of diverse perspectives from underrepresented groups such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers, people with disability and LGBTQIA+ researchers in academia, all of whom suffer from lack of representation in senior leadership positions.32 Without role models at higher levels, researchers belonging to minority groups may feel uncertain about promotion criteria and are less inclined to pursue career advancement. Marginalised individuals face the added burden of having to advocate for their rights, assert their place in research, often struggle to fit into the traditional academic mould, and are often called upon to advocate for their community.30 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander researchers are frequently asked to take on workloads beyond their formal roles or employment arrangements, for example, contribute to specific events institution-wide, connect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ and communities with institutions, become committee members, run cultural awareness training for staff and students, be a representative at events (for example, NAIDOC event), revise and review Aboriginal employment plans and Reconciliation Action Plans. All of these activities are time consuming and are rarely appropriately remunerated or recognised in assessment metrics or as part of recruitment approaches.32

EMCRs and diversity groups have indicated a need for enhanced transparency in how institutions incorporate research assessment into promotion criteria, recruitment processes and career progression.30

Promotion committees with a diverse makeup are more likely to respond with empathy and understanding towards marginalised individuals. The creation of specific career pathways and clear guidelines can support people with diverse needs seeking to progress their careers.27

4.4.2 Implementation

Rewarding and recognising positive contributions to the institutional research culture and the use of responsible research practices can be achieved through formal processes such as appointments, promotions and awards, and through informal processes such as peer recognition. Suggested activities to achieve gradual improvements in these areas are highlighted in Table 8.

| Phase | Suggested activities |

|---|---|

| Make it possible |

|

| Make it easy |

|

| Make it normative |

|

| Make it rewarding |

|

| Make it required |

|

4.4.3 Self-reflection questions

The following sample self-reflection questions could be used as prompts for leaders to determine their stage of implementation as outlined in Table 8.

Sample self-reflection questions:

- What criteria does the institution have for rewarding and recognising responsible research practices when making appointments, promotions, awards and informal peer recognition?

- Has the institution developed clear guidance for staff involved in recruitment and promotion decisions that explicitly cautions against the inappropriate use of publication metrics and encourages them to value a full and diverse range of research outputs and contributions?

- Have leaders informed researchers that hiring and promotion criteria will focus on responsible research practices and hence a diverse range of research outputs and contributions?

- How do the leaders recognise and/or reward examples of behaviours that contribute to a positive research culture, good mentorship and supervision?

- How are administrative and support units recognised and rewarded for positive contributions to the institutional research culture and support for high-quality research?

- What requirements regarding assessment criteria relevant to research quality exist in formal institutional policies for hiring and promotion?

4.4.4 Case studies and scenarios

When the QUEST (Quality-Ethics-Open Science-Translation) Center for Transforming Biomedical Research at the Berlin Institute of Health in Germany evaluates applications for hiring and tenure, criteria include responsible research practices, with questions covering practices such as publishing of null results, open data and stakeholder engagement.42 QUEST office staff screen applications and participate in hiring committee meetings to support committee members in understanding, evaluating, and applying the criteria.

University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands undertook a consultative process with staff to develop a new framework for evaluating staff for promotions that moved away from bibliometrics and formally required qualitative indicators and a descriptive portfolio.43 Along with other elements, Utrecht candidates now provide a short essay about who they are and what their plans are as faculty members. Candidates must discuss their achievements in terms of the following domains with bibliometrics comprising only one domain:

- managerial responsibilities and academic duties, for example, conducting reviews for journals and contributing to internal and external committees

- teaching and supervision of students, for example, how much time is devoted to students and any courses they have developed,

- clinical work undertaken, for example, involvement in organising clinical trials and research into new treatments and diagnostics

- entrepreneurship and community outreach.

Reported outcomes of this change are:

- group leaders engaging with, debating about and then embracing the new framework

- EMCRs engaging with the framework and proposing forward-looking ideas to improve scientific outcomes

- students organising a brainstorming session with high-level faculty members about how to change the medical and life-sciences curriculum to incorporate reward-and-incentive structures

- the PhD council choosing a ‘supervisor of the year’ on the basis of the quality of supervision, instead of the previous practice of the highest number of PhD students supervised.

The leaders of a research group were aware that although they had invited a speaker to their regular meeting to speak about transparent research behaviours and had followed up with an email with links to resources, there had been no change in uptake of those behaviours. They decided to implement a reward scheme, where any member of the research group could receive $100 as a dining/movie/retail voucher, or as a contribution to their research account, for:

- pre-registering their research project

- preparing a data management plan, including to share the data at the end of the project

- depositing a preprint of any manuscript

- making any publications openly accessible

- sharing data from the project based on the FAIR principles2

- publishing code from the project.

When communicating about this reward scheme, the research group leaders were careful to stress that it was not intended as a reward based on metrics. Because each of the behaviours that were eligible under the reward scheme were measurable, the leaders were able to see a quantifiable improvement in the behaviours after 12 months.

4.5 Communication

Desired outcomes

- Staff are aware of and understand how the institution’s policies and procedures help to shape a research culture that is conducive to the conduct of high-quality research.

- Information is publicly available about the institution’s policies and procedures relevant to research culture and responsible research practices.

4.5.1 Introduction

Transparent and regular communication with all staff and students about institutional policies and procedures is integral to conveying the institution’s expectations and shaping research culture. This can be achieved within the institution through formal channels with staff and students, as well as informally within research groups, faculties/schools and through peer networks. Making the institution’s policies and procedures publicly available, wherever possible, contributes to sharing of information within the sector. While awareness raising will not bring about cultural change on its own, when staff are provided with the guidance and support to implement policies and procedures, it makes an important contribution.

4.5.2 Implementation

Suggestions for how leaders can enhance communication about relevant institutional policies and procedures both internally and externally are provided in Table 9. It does not include suggestions for how researchers could better communicate with each other or communicate about their research activities.

| Phase | Suggested activities |

|---|---|

| Make it possible |

|

| Make it easy |

|

| Make it normative |

|

| Make it rewarding |

|

| Make it required |

|

4.5.3 Self-reflection questions

The following sample self-reflection questions could be used as prompts for leaders to determine their stage of implementation as outlined in Table 9.

Sample self-reflection questions:

- What sort of information and guidance on research culture and responsible research practices does the institution provide to the staff and students?

- How do leaders encourage communication between research groups/disciplines/institutions to facilitate exchange of ideas and information about following and improving research practices, particularly for interdisciplinary and collaborative research?

- How are reports about analysis of matters related to research quality within the institution disseminated to all those within the institution?

- What is the institution’s commitment to implementing internationally recognised principles that promote responsible research practices?

- To what degree does the institution make policies and procedures relevant to research culture and research practices publicly available as exemplars of good practice?

4.5.4 Case studies and scenarios

To address misconceptions surrounding research involving the use of animals, the Openness Agreement on Animal Research and Teaching in Australia was launched in 2023.44 NHMRC is a supporter of this agreement. Similar openness agreements have been developed for other countries.45 Internationally, the outcomes from openness agreements include:

- better public access to information about animals in research, directly from those who do the research

- a greater understanding and appreciation of the role of animal care staff, both in and outside the sector

- increased profile of animal facilities within their establishments, leading to greater investment and better animal welfare

- better access to see inside animal facilities (for those interested in this work)

- fewer reactive communications on the use of animals in research, due to more information proactively placed in the public domain.44

An analysis of the issues being reported by staff at a research institution showed that the majority related to miscommunication such as misunderstandings between scientific collaborators, and how best to engage with the public. To address these issues, institutional and research leaders agreed that these issues could be improved if better procedures were put in place to optimise communication and collaboration. They supported the development of a Research Quality Promotion Plan (RQPP), based on SOPs4RI consortium’s Research Integrity Promotion Plan,46 to guide the development of appropriate policies and procedures. The Research Office was given responsibility for designing an RQPP. The plan comprised:

- a description of the current situation, including the policies and procedures already in place and how effective they are

- areas in need of improvement

- a detailed plan for future activities.

The plan for future activities involved:

- specifying the change-related goals

- employee participation and agreement on a shared outcome of the change

- description of the institutional set-up for implementing the envisioned change

- finding the right tools in the SOPs4RI toolbox47 that match the goals

- specifying actions to be taken by specific people

- a set of indicators or targets to be used for evaluating the effectiveness of the change process.

The outcome was implementation of sound policies and procedures to guide effective and transparent communication and collaboration between staff. The policies and procedures were communicated regularly to all institutional staff via internal staff communications and newsletters and were made available on the institution’s internal and external websites.

The Open Science Framework (OSF) was created by Brian Nosek and his graduate student, Jeff Spies, with the aim of preventing the loss of research material, while creating incentives for preservation and transparency.48 It is a free open-source web application that helps individuals and research teams organise, archive, document and share their research materials and data. Information connected to an OSF project might include study materials, analysis scripts and data, as well as a wiki, and attached files, submissions to institutional review boards, notes about research goals, posters, lab presentations or pre-prints. Because each action is logged and version histories of the wikis and files kept, the history of the research process is recoverable, and materials are not lost. This means that the work is more easily reproduced either by the project authors or by others.

The OSF allows research groups to make their scripts, code and data available to the public, enabling others to reproduce their analyses and findings or reanalyse the data for their own purposes. To encourage such transparency of findings, the OSF includes incentives such as statistics documenting the number of project views and files downloads for public projects, and a novel citation type called a ‘fork’ that registers when others are using and extending your research outputs. As Nosek says, ‘without openness and reproducibility in the scientific process, we are forced to rely on the credibility of the person making the claim, which is not how it should be. The evidence supporting the claim needs to be available for evaluation by others, hence the need to help create a research culture that is open and transparent.’48

4.6 Monitoring, evaluation and reporting

Desired outcomes

Institutions have processes in place to:

- monitor, evaluate and report on their progress in implementing the suggested activities outlined in this Guide

- regularly review progress over time

- implement recommendations on how to improve progress.

4.6.1 Introduction

Monitoring, evaluation and reporting by institutions about their progress in implementing the suggested activities in this Guide will allow them to identify strengths and weaknesses, areas for improvement and potential issues; to track progress; and to measure positive changes.

Cultural change may be slow. Consequently, monitoring, evaluation and reporting efforts need to be planned for and supported in the long term. This requires an enduring institutional commitment to both cultural change and evaluation.

Many institutions already have processes and initiatives in place to support the conduct of high-quality research and continually improve research culture. As approaches, policies and processes may vary between institutions, this Guide allows for flexibility in its application. It is therefore expected that there will be variation in the way that each institution chooses to monitor, evaluate and report on their progress.

For those institutions that lack a unit focused on evaluation, the ‘Resources’ section (Section 6.2.9) includes information about useful resources and toolkits provided by the Commonwealth and state governments and the Global Evaluation Initiative.

4.6.2 Implementation

The values and elements outlined in this Guide provide a structure for a monitoring framework. That is, the monitoring framework could capture data relating to the key values (Table 10) or data relating to each of the five elements identified as contributing to an institution’s research culture (Table 11).

Suggestions for how institutions can achieve gradual improvements in the monitoring, evaluation and reporting about their progress in implementing the suggested activities in this Guide are highlighted in Table 12.

| Phase | Suggested activities |

|---|---|

| Make it possible |

|

| Make it easy |

|

| Make it normative |

|

| Make it rewarding |

|

| Make it required |

|

4.6.3 Self-reflection questions

The following sample self-reflection questions could be used as prompts for leaders to determine their stage of implementation as outlined in Table 12.

Sample self-reflection questions:

- What processes does the institution have in place to monitor, evaluate and report on the progress in implementing the suggested activities outlined in the Guide?

- Who within the institution is responsible for making recommendations about allocation of resources for monitoring and evaluation, receiving reports of the outcomes of evaluation, directing implementation of the monitoring and evaluation framework, and making changes required as a consequence of the evaluation activities?

- How will the institution ensure that progress is reviewed regularly, and quality improvement opportunities are applied?

- What are the institution’s long-term commitments to conducting monitoring, evaluation and reporting efforts?

4.6.4 Case studies and scenarios

There are various ways of evaluating a course on the responsible conduct of research, ranging from recording student attendance to assessing their attitudinal changes.

A decision should be made about whether you are going to evaluate the effectiveness of the course delivery or assess actual learning and/or change. The simplest forms of evaluation are paper or online surveys whose questions often focus on program mechanics, delivery by presenters and completion of required activities. They don’t indicate whether any learning has actually occurred and whether behaviours will change as a result of the education and training. In contrast, qualitative evaluation questions require written responses and take more time and effort from the respondent. However, they can provide useful information on, for example, how the discussions and readings were received.

Since there are significant benefits to be gained from determining whether any learning is taking place, it may be worthwhile collecting standardised data over several years to look for a cumulative effect (summative or outcome evaluation).

When formulating questions to assess what has been learned, it is useful to categorise the types of learning that can take place into the following: knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours, and possibly beliefs. Then carefully specify the intended learning outcomes from each session under each of these categories. It is important that these learning outcomes are designed to be measurable. As it is particularly difficult to measure impact on people’s behaviours, it is useful to formulate questions that ask about their anticipated future behaviours. With carefully designed questions, it should be possible to obtain useful feedback on how participants are receiving and processing the information presented, and this can then be used to continually improve the teaching process.

Following the introduction of a Data Management and Sharing Policy by the US National Institutes of Health in 2023, the Stanford Program for Rigor and Reproducibility (SPORR) at Stanford Medicine, in collaboration with Stanford’s Lane Library, conducted focus groups to understand the data sharing and management practices of Stanford early career researchers and the support they might need to follow NIH policy.51 The results showed that participants:

- wrote data management plans only when required by an ethics committees or funding body

- shared data only when required by funders or journals

- generally used cloud-based services to store their research data and to share with collaborators or statisticians but were unsure about the security of these services and the best methods for using them

- emphasised the effort required to prepare and store data properly

- feared that, without dedicated funding, incentives or mandates to make these practices required, investing the time in data management might put them at a disadvantage for career advancement.

The participants in the focus groups suggested that the following web resources would be helpful:

- one main data page that collates all data policies, services and resources

- data management plan templates

- flowcharts for data sharing and management per data type

- guidance on how to initiate data discussions at their lab.

These results from the focus groups will now be used to develop a survey that will be sent to all members of Standford School of Medicine.

1 Nosek B. Strategy for culture change. June 2019. Center for Open Science. Accessed on 14 November 2024 from: https://www.cos.io/blog/strategy-for-culture-change

2 FAIR Principles. GO FAIR [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/

3 CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance. GIDA: Global Indigenous Data Alliance. [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.gida-global.org/care

4 UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science [updated 21 Sep 2023] [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from https://en.unesco.org/science-sustainable-future/open-science/recommendation

5 NHMRC Workshop report: Strengthening and growing capacity and capability of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health researchers, Melbourne University Business School, 16-17th May 2018 [Internet] Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-advice/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-health/capacity-and-capability-building-and-strengthening

6 National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Innovate: Reconciliation Action Plan II April 2022-April 2024. [Internet] Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Accessed 13 Dec 2024 from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/reconciliation-action-plan-2022-24

7 Reconciliation Australia. Reconciliation Action Plans. [Internet] Accessed 5 Mar 2025 from: https://www.reconciliation.org.au/

8 University of Glasgow. Research and Innovation Services: research culture. [Internet]. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/ris/researchculture/

9 University of Glasgow. Institutional strategic priorities for research culture 2020-2025. [Internet]. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_705595_smxx.pdf

10 Stanford Medicine: Stanford Program on Research Rigor & Reproducibility. [Internet]. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://med.stanford.edu/sporr/about/missionstrategyvalue.html

11 Supervision: A guide supporting the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research. National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council and Universities Australia. Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra. Published 2019, Publisher NHMRC. [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-code-responsible-conduct-research-2018

12 Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research, 2018 Guide to Managing and Investigating Potential Breaches of the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research, 2018, and NHMRC policy on misconduct related to NHMRC funding, 2016. [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/research-policy/research-integrity

13 NHMRC: Survey of research culture in Australian NHMRC-funded institutions. 2020. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/research-policy/research-quality

14 Ryan T, Ewen S, Platania-Phung C. It wasn’t just the academic stuff, it was life stuff: the significance of peers in strengthening the Indigenous health researcher workforce. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education. 2020; 49(2):135-144 [Internet] https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.14

15 University of Cambridge. Data Champions. [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from https://www.data.cam.ac.uk/intro-data-champions

16 American Statistical Association. Overview of statistics as a scientific discipline and practical implications for the evaluation of faculty excellence. A position paper of the American Statistical Association. 5 Jan. 2018 Accessed on 16 Dec 2024 from: https://www.amstat.org/asa/files/pdfs/POL-Statistics-as-a-Scientific-Discipline.pdf

17 Bruckner T. Tips and tricks for improving clinical trial reporting from Karolinska university. 2023 TranspariMED. [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.transparimed.org/single-post/karolinska-university

18 Possmark S, Martinsson Bjorkdahl C. Responsible reporting of clinical trials: Reporting at Karolinska Institutet is well underway. Lakartidningen [Internet] 2023;120: 23007. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://lakartidningen.se/klinik-och-vetenskap-1/artiklar-1/temaartikel/2023/05/ansvarsfull-rapportering-av-kliniska-lakemedelsprovningar/

19 UK Reproducibility Network, Terms of reference, [Internet] 2023 Apr. Accessed 5 October 2023 from: https://www.ukrn.org/terms-of-reference/

20 Committee UKRNS. From grassroots to global: A blueprint for building a reproducibility network. PLOS Biology [Internet] 2021;19(11): e3001461. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001461

21 Australian Reproducibility Network. [Internet] Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.aus-rn.org/

22 Héroux ME, Butler AA, Cashin AG, McCaughey EJ, Affleck A, et al. Quality Output Checklist and Content Assessment (QuOCCA): a new tool for assessing research quality and reproducibility. BMJ Open [Internet] 022;12:e060976. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-060976

23 Kuei-Chiu Chen, Hester L A dramatized method for teaching undergraduate students responsible research conduct, Accountability in Research [Internet] 2023;30:3, 176-198, https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2021.1981871

24 Erasmus University Rotterdam. Dilemma game. Professionalism and Integrity in Research. [Internet]. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.eur.nl/en/about-eur/policy-and-regulations/integrity/research-integrity/dilemma-game

25 Weeks KL, Henstridge DC, Salim A, Shaw JE, Marwick TH, McMullen JR. CORP: Practical tools for improving experimental design and reporting of laboratory studies of cardiovascular physiology and metabolism. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology [Internet] 2019;317:3, H627-H639. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00327.2019

26 ARRIVE guidelines. [Internet] Accessed on 19 Dec 2024 from: https://arriveguidelines.org/

27 Australian Council of Learned Academies (2023), Research Assessment in Australia: Evidence for Modernisation. A report to the Office of the Chief Scientist, Australian Government, Canberra. Accessed 13 Nov 2024 from: https://acola.org/research-assessment/

28 Science Europe. Position Statement and Recommendations on Research Assessment Processes. 2020. [Internet]. Accessed 21 Nov 2023 from: https://www.scienceeurope.org/our-resources/position-statement-research-assessment-processes/

29 Moher D, Bouter L, Kleinert S, Glasziou P, Sham MH, et al. The Hong Kong Principles for assessing researchers: Fostering research integrity. PLOS Biology [Internet]. 2020;18(7): e3000737. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000737

30 Wellcome Trust. Guidance for research organisations on how to implement responsible and fair approaches for research assessment [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from https://wellcome.org/grant-funding/guidance/open-access-guidance/research-organisations-how-implement-responsible-and-fair-approaches-research

31 Edwards MA, Siddhartha R. Academic Research in the 21st Century: Maintaining scientific integrity in a climate of perverse incentives and hypercompetition. Environmental Engineering Science [Internet]. 2017 Jan;51-61. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: http://doi.org/10.1089/ees.2016.0223

32 Diversity Council Australia. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples- Leading Practice: Understand the 10 truths to centre Indigenous Australians’ voices to create workplace inclusion. [Internet] Accessed 7 Mar 2025 from: https://www.dca.org.au/resources/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples/aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-peoples-leading-practice

33 Schmidt R, Curry S, Hatch A. Research Culture: Creating SPACE to evolve academic assessment eLife [Internet] 2021 Sep 23. 10:e70929 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.70929

34 The Einstein Foundation Berlin. The Einstein Foundation Award for Promoting Quality in Research. [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://www.einsteinfoundation.de/en/award/

35 Berlin Institute of Health. The QUEST 1,000 Euro NULL Results Award.[Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://www.bihealth.org/en/translation/innovation-enabler/quest-center/calls-and-awards/quest-calls-and-awards/null-and-replication

36 Berlin Institute of Health. The QUEST 1,000 Euro Preregistration Award.[Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://www.bihealth.org/en/translation/innovation-enabler/quest-center/calls-and-awards/quest-calls-and-awards/preregistration

37 DORA: The Declaration on Research Assessment [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://sfdora.org/

38 CoARA: Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://coara.eu/

39 Hicks D, Wouters P, Waltman L, et al. Bibliometrics: The Leiden Manifesto for research metrics. Nature [Internet] 2015; 520:429–431. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://doi.org/10.1038/520429a

40 United Kingdom Reproducibility Network Supervisory Board, 2021. UKRN Statement on Responsible Research Evaluation. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/4pqwv

41 United Kingdom Reproducibility Network, 2021. UKRN Statement on Rewards and Incentives for Open Research. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/v5jrm

42 Strech D, Weissgerber T, Dirnagl U, on behalf of QUEST Group (2020) Improving the trustworthiness, usefulness, and ethics of biomedical research through an innovative and comprehensive institutional initiative. PLOS Biology [Internet]. 2020 Feb 11;18(2): e3000576. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000576

43 Benedictus R, Miedema F, Ferguson M. Fewer numbers, better science. Nature [Internet] 2016; 538, 453–455. https://doi.org/10.1038/538453a

44 ANZCCART. Openness Agreement on Animal Research and Teaching in Australia. [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://anzccart.adelaide.edu.au/openness-agreement

45 Lear AJ, Hobson H. Concordat on Openness on Animal Research in the UK. Annual Report 2022 [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://concordatopenness.org.uk/resources

46 SOPs4RI consortium. How to create and implement a research integrity promotion plan (RIPP). A guideline (ver. 2.0) [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://sops4ri.eu/wp-content/uploads/Implementation-Guideline_FINAL.pdf

47 SOPs4RI consortium. Toolbox for research integrity. V5.0 (CC BY 4.0) [Internet]. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from https://sops4ri.eu/toolbox/

48 Nosek BA. Improving my lab, my science with the open science framework. Association for Psychological Science [Internet]. 2014 Feb 28. Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/improving-my-lab-my-science-with-the-open-science-framework

49 NSW Government website: Evaluation resource hub. Evaluation design and planning. Accessed on 17 Dec 2024 from: https://education.nsw.gov.au/teaching-and-learning/professional-learning/pl-resources/evaluation-resource-hub/evaluation-design-and-planning

50 McGee R. Evaluation in RCR training- are you achieving what you hope for? Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education [Internet]. 2014 Dec 15;15(2). Accessed 22 Nov 2023 from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/jmbe.v15i2.853

51 Stanford School of Medicine. Stanford Program on Research Rigor and Reproducibility. Focus group and Stanford-wide survey on data sharing and management practices. [Internet] Accessed on 20 Nov 2024 from: https://med.stanford.edu/sporr/monitoring.html?tab=proxy#focus-groups-and-stanford-wide-survey-on-data-sharing-and-management-practices