Inflammation of the stomach (gastritis) and peptic ulcers have been significant sources of illness throughout recorded history. Up until the 1980s, they were thought to be caused by excess stomach acid, stress, or dietary factors such as spicy food or alcohol. However, NHMRC-funded researchers at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) played key roles in the Nobel Prize winning discovery that ulcers are ultimately caused by a bacterial infection and that they can be cured using antibiotics. This research has led to the virtual elimination of peptic ulcer disease throughout the world, where treatment is available.

Origin

Direct knowledge that the human digestive system is full of microscopic living creatures extends at least as far back as 1681, when Antonie van Leeuwenhoek – a pioneering microscopist and microbiologist – observed “more than 1000 living animalcules” when studying his own faecal material. Two years later, Leeuwenhoek also described microscopic organisms in a sample he’d obtained from his mouth.1

Over time, medical bacteriologists came to consider that any microorganisms living in the human digestive tract were likely to be playing a harmful role. In 1964, however, Rockefeller University microbiologist Rene Dubos proposed the theory that within healthy animals there exists:

. . . an abundant and characteristic microflora, not only in the large intestine but also in all the other parts of the digestive tract . . . they become so intimately associated with the various digestive organs that they form with them a well-defined ecosystem in which each component is influenced by the others and by the environmental conditions.2

Because many of the microorganisms that live in the digestive system are very difficult to grow anywhere else, and therefore difficult to study in the laboratory, Dubos’s theory was difficult to test and substantiate with evidence. In 1967, and working in Dubos’ laboratory, Australian postdoctoral researcher Adrian Lee developed one of the first anaerobic culture cabinets and grew bacteria found in the mouse intestinal tract.3

In 1968, Lee was recruited to UNSW by his former PhD supervisor Professor Graeme Cooper, who had just commenced as UNSW’s Professor of Microbiology. Under Cooper’s direction but guided by Lee’s experience in the US, a key focus for their laboratory work became the advancement of knowledge about the gastrointestinal ecosystem.

Investment

NHMRC provided a succession of grants to researchers at UNSW to support their investigations of the gastro-intestinal ecosystem. These researchers included Graeme Cooper, Adrian Lee, Hazel Mitchell and Stuart Hazell. In addition, NHMRC provided funding to support the related research activities of Barry Marshall and Robin Warren at the University of Western Australia (UWA) and Royal Perth Hospital.

The PDF poster version of this case study includes a graphical time showing NHMRC grants provided and other events described in the case study.

Research

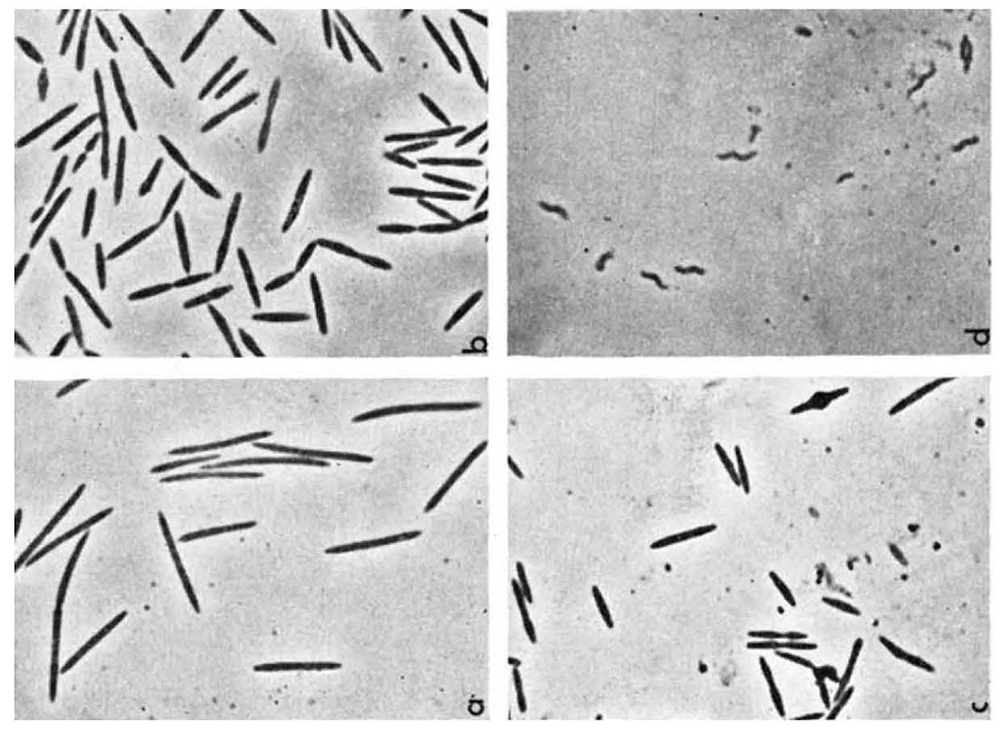

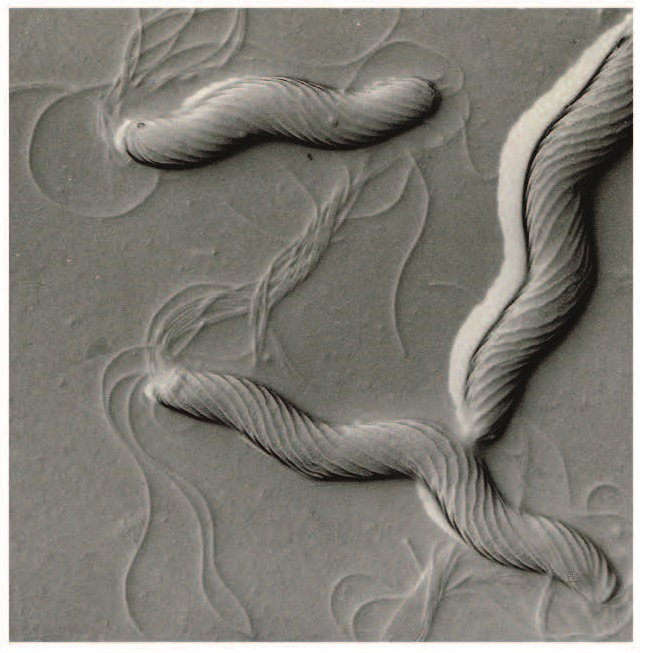

Cooper, Lee and their team began their investigations of the gastrointestinal ecosystem by studying bacteria that lived in the walls of the intestine. Some had a rod-like shape, while others – which came to be known as ‘Helicobacters’ (i.e. helix-shaped bacteria) – had a spiral shape that assisted them to burrow into the intestinal wall.

During the 1970s, the UNSW team developed expertise on a range of spiral-shaped bacteria, including Helicobacter muridarum and Campylobacter jejuni, the latter being a leading cause of bacterial foodborne gastroenteritis world-wide and a major public health concern.

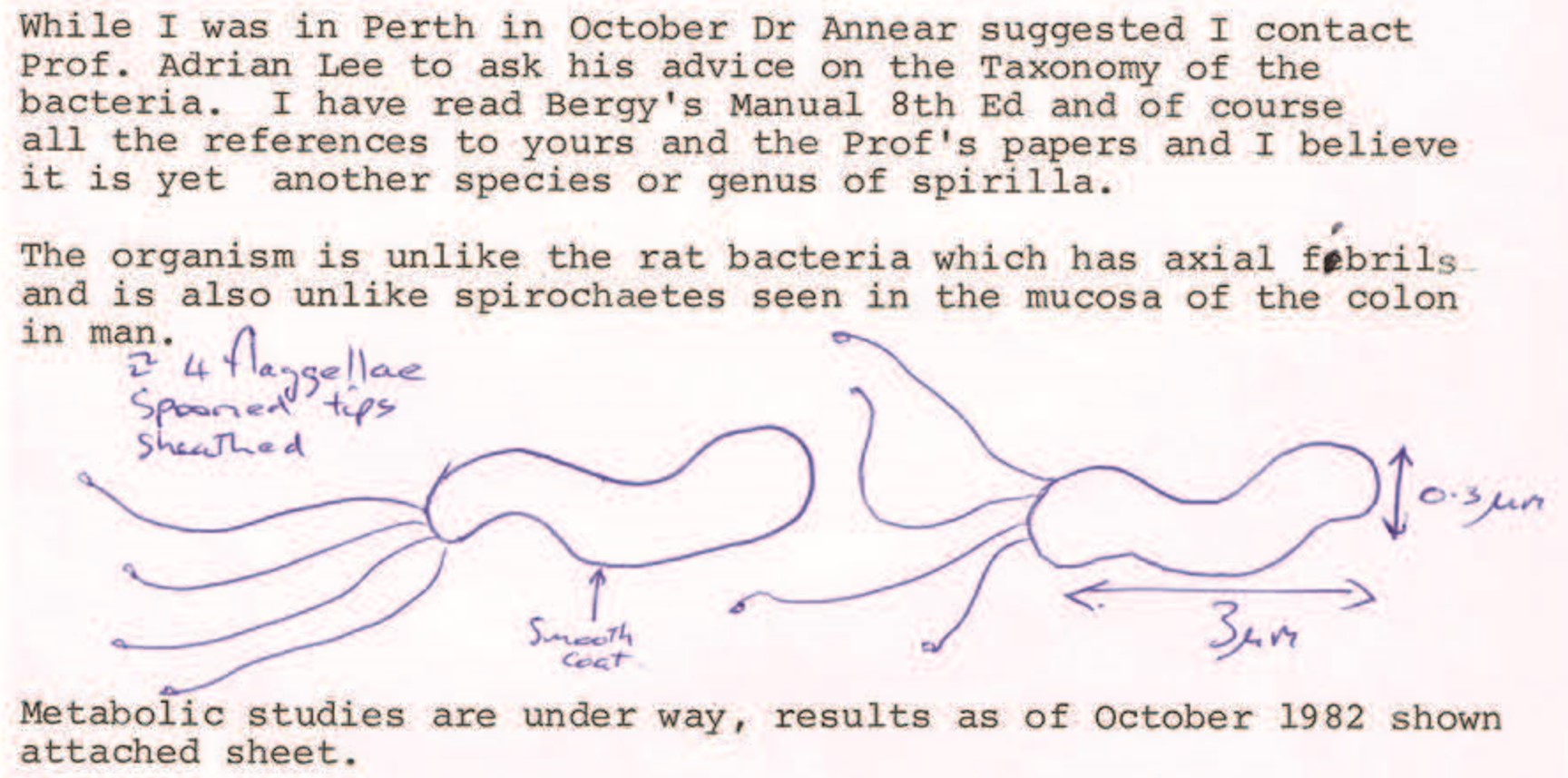

In 1982, Australian clinician and researcher Barry Marshall, based at Royal Perth Hospital, contacted the UNSW team seeking their assistance in identifying a particular spiral-shaped bacteria that he and colleague Robin Warren had obtained from the human stomach, and which they had been able to grow in the laboratory using a method that the UNSW team had developed. Marshall and Warren thought these bacteria could be playing a role in causing gastritis and peptic ulcers.

Informed by this idea, UNSW PhD student Stuart Hazell began focusing his research on the new bacteria (which came to be known as Helicobacter pylori) and began attempting to grow it in the laboratory. Using biopsies (tissue samples) provided by the gastroenterology department at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney, Hazell undertook the first studies explaining H. pylori’s mechanism of colonizing the stomach and he devised one of the first tests for diagnosis, called the urease test, which is still being used today for detecting the presence of H. pylori in the stomach.

In 1990, the UNSW team were able to demonstrate that a similar organism, Helicobacter felis, was commonly found in the stomach of cats and caused inflammation. This bacteria was used internationally as a basis for Helicobacter research until 1997, when UNSW team members Hazel Mitchell and Jani O’Rourke improved on it, isolating a culture of H. pylori that would grow in mice and which is still widely used.

Mitchell also worked with biopsies from St Vincent’s Hospital to understand H. pylori’s epidemiology (i.e. how it was being transmitted and spread) and she devised and commercialised one of the first antibody serology tests for the organism, enabling clinicians around the world to diagnose H. pylori infection.

Marshall and Warren had proposed that H. pylori infection could cause cancer, and the UNSW team’s mouse model showed that long-term H. felis infection could cause gastric lymphoma. Lee became one of a number of Helicobacter researchers on an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) working group evaluating carcinogenic (cancer causing) risks to humans. Their evaluation, which ended in 1994, concluded that there was sufficient evidence that H. pylori could cause cancer, and it became the first recognised microbial carcinogen.

Translation

During the early 1980s, St Vincent’s Hospital gastroenterologist Tom Borody was seeing 2-3 patients with peptic ulcers each day. The treatment and management of acute and chronic peptic ulcers formed a major part of his daily medical practise. Following discussions with Hazell about H. pylori, Borody realised that it should be possible to develop a cure for peptic ulcers.

Borody recognised that, while Marshall had provided evidence that swallowing the bacteria could lead to damaged mucosa, ulcers were not induced. The only way to prove that H. pylori caused ulcers was to develop treatment that controlled the bacteria, and show that ulcers not only healed, but stayed healed.

The treatment that Borody and his colleagues developed came to be known as the ‘Triple Therapy’. It consisted of two antibiotics plus a proton pump inhibitor to reduce stomach acid. By 1986, this treatment was being used extensively in Australia for H. pylori control and was also quickly adopted overseas.

In 1989, Borody and colleagues reported that the use of Triple Therapy led to the eradication of H. pylori and the subsequent healing of ulcers5. In 1990, they reported that H. pylori eradication cured duodenal ulcers6. In 1994, they published a 4–6 years post-eradication report, confirming ulcers remained healed and that the re-infection rate was only about 0.1% per annum.7

To address problems associated with antibiotic resistance, Borody and colleagues later developed a ‘Quad Therapy’ which successfully eradicated H. pylori in 90% of those with resistant bacteria. Further innovation by this team increased the success rate to 97%.8

Outcomes and impacts

Before the discovery of H. pylori, peptic ulcers were an enormous problem. Medical and surgical wards in Australian hospitals treated many patients for peptic ulcer disease, but these treatments were based upon the incorrect understanding that the disease was caused by stress, diet and other lifestyle factors. Bacteria were not suspected because the stomach was thought to be sterile, owing to its harsh acidic environment9,10

It is now understood that the human digestive system, including the stomach, permanently hosts a vast number, and many different kinds, of microbes and that its healthy functioning depends upon a thriving ecosystem. This ecosystem can cease to thrive for a variety of reasons, including the host’s genetics, their immune system, the specific microbes that make it up and their virulence factors, plus a range of lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, sleep, smoking and alcohol consumption.

While the stomach microbiomes of more than 50% of the world’s population may include H. pylori, most people will not develop symptoms of ill health from this bacterium. It is only when the stomach’s ecosystem becomes unbalanced, with H. pylori coming to dominate other gastric microbes, that problems start to emerge. These problems can include chronic active gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and gastric adenocarcinoma. H. pylori has been shown to cause more than 90% of duodenal ulcers, up to 80% of gastric ulcers and up to 89% of intestinal type gastric adenocarcinomas. 11,12

The discovery of H. pylori and the development of an effective and low-cost means of treating it (Triple Therapy) was highly influential for Australian clinicians. In 2004, the Medical Journal of Australia – a leading journal read by Australian clinicians and researchers – reported that 4 of its top 10 most cited articles during the past 90 years related to H. pylori.13

These discoveries also brought enormous benefits to Australia and internationally through reductions in the prevalence of H. pylori infection and in associated morbidity, mortality, hospital admissions and health care. In Australia, between 1990 and 2015, treatment of peptic ulcer disease by Triple Therapy is estimated to have prevented 18,665 deaths and saved 258,887 life years and 33,776 productive life years. The total savings, over the 26-year period, including direct and indirect costs, are calculated to be $10.03 billion, equating to an average annual saving of $393 million.14

While much progress has been made to prevent peptic ulcer disease, gastric adenocarcinoma continues to pose a major global health challenge, accounting for over one million deaths annually.15 NHMRC continues to fund research into H. pylori and its role in gastric disease and cancer.16

Researchers

Professor Geoffrey Cooper

Geoffrey Norton Cooper (1929-2024) graduated from the University of Melbourne with a Masters degree in science and a PhD. After heading the university’s Microbiology Diagnostic Unit, in 1968 Cooper moved to UNSW to take up the Foundation Chair of Medical Microbiology. Cooper served on various World Health Organisation (WHO) expert committees with a focus on typhoid, cholera and dysentery.

Professor Adrian Lee AM

Adrian Lee (1941-2023) completed a PhD at the University of Melbourne then a postdoctoral fellowship at Rockefeller University in New York. He was Professor of Microbiology at UNSW from 1990 to 2006 and Pro Vice-Chancellor (Education and Quality Improvement; 2000-2006).

Lee acted as a WHO consultant in the area of medical education and was one of the first recipients of the UNSW Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Teaching Excellence. He was also the inaugural recipient of the Distinguished Teaching Award of the Australian Society for Microbiology. Lee was an Australian Universities Quality Agency auditor and in 2008 was awarded a Career Achievement Award by the Australian Learning and Teaching Council. In 2024, Lee was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia.

Professor Barry Marshall AC

Barry James Marshall completed a medical degree in 1974 at UWA. In 1979, Marshall was appointed Registrar in Medicine at the Royal Perth Hospital. After then working at Fremantle Hospital, Marshall undertook research at Royal Perth Hospital (1985–1986) and at the University of Virginia in the US before returning to Australia. In 2007, Marshall was appointed Co-Director of The Marshall Centre for Infectious Diseases Research and Training also accepted a part-time appointment at the Pennsylvania State University. In 2007, Marshall was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia.

Barry Marshall and Robin Warren were jointly awarded the 2005 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. When Warren and Marshall received the Nobel prize, Adrian Lee accompanied them to Stockholm where he was an honoured guest.

Professor J Robin Warren AC

John Robin Warren (1937-2024) received his medical degree from the University of Adelaide. He trained at the Royal Adelaide Hospital and became a Registrar in Clinical Pathology at the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science. In 1963, Warren was appointed Honorary Clinical Assistant in Pathology and Honorary Registrar in Haematology at Royal Adelaide Hospital. Subsequently, he lectured in pathology at the University of Adelaide and then became Clinical Pathology Registrar at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. Warren became a senior pathologist at the Royal Perth Hospital, where he spent the majority of his career. In 2007, Warren was appointed a Companion of the Order of Australia.

Professor Tom Borody

Thomas J Borody graduated in medicine from UNSW in 1974. He then studied tropical medicine at the University of Sydney and gained clinical experience in the Solomon Islands in 1978 in general parasitology and the treatment of malaria, tuberculosis and leprosy. In 1984, after working at St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney, Borody founded the Centre for Digestive Diseases (CDD). Borody undertook postgraduate research at the Garvan Institute of Medical Research. He undertook three years of clinical research at the Mayo Clinic in the US and graduated with a PhD in 2005.

Professor Hazel Mitchell

Professor Hazel Mitchell was awarded a PhD in Microbiology and Immunology from UNSW in 1993. She was Head of Medical Microbiology in the School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Science, UNSW and was Professor of Medical Microbiology at UNSW from 2006 to 2020. Mitchell played a major role in convening and teaching Medical Microbiology to Science and Medical students. For more than 25 years her research focused on the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori including studies investigating the epidemiology, pathogenesis and the role of bacterial and host genetic factors in gastric cancer. In 1996, Mitchell was a founding organiser of the Western Pacific Helicobacter pylori study group and was convenor of the first meeting in Guangzhou, China and international scientific adviser for subsequent meetings in Malaysia, Indonesia, Australia, Japan and Thailand.

Other researchers

Other researchers that contributed to the impacts described in this case study include Professor Stuart Hazell and Dr Jani O’Rourke.

Partner

This case study was developed with input from Natalia Castaño Rodríguez and in partnership with the University of New South Wales.

References

The information and images from which impact case studies are produced may be obtained from a number of sources including our case study partner, NHMRC’s internal records and publicly available materials. Key sources of information consulted for this case study include:

1 Farré-Maduell E, Casals-Pascual C. The origins of gut microbiome research in Europe: From Escherich to Nissle. Human microbiome journal. 2019 Dec 1;14:100065.

2 Dubos R, Schaedler RW. The digestive tract as an ecosystem. American Journal of Medical Sciences, 1964, Vol. 248, 267-272

3 Lee A, Gordon J, Dubos R. Enumeration of the oxygen sensitive bacteria usually present in the intestine of healthy mice. Nature. 1968 Dec 14;220(5172):1137-9

4 Lee A. Adventures with spiral bugs and 'Helicobacter'. In Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 2021 Jun 1 (Vol. 154, No. 481/482, pp. 34-43). Sydney: Royal Society of New South Wales

5 Borody TJ, Cole P, Noonan S et al. Recurrence of duodenal ulcer and Campylobacter pylori infection after eradication. 1989. Med J Aust, 151(8), 431–435.

6 George LL, Borody TJ, Andrews P et al. Cure of duodenal ulcer after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. 1990. Med J Aust, 153(3), 145–149.

7 Borody TJ, Andrews P, Mancuso N et al. Helicobacter pylori reinfection rate, in patients with cured duodenal ulcer. 1994. Am J Gastroenterol, 89(4), 529–532.

8 Borody T. 'Helicobacter pylori' causes peptic ulcers. In Journal and proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 2021 Jun 1 (Vol. 154, No. 481/482, pp. 44-46). Sydney: Royal Society of New South Wales.

9 Fakharian F, Asgari B, Nabavi-Rad A, Sadeghi A, Soleimani N, Yadegar A, Zali MR. The interplay between Helicobacter pylori and the gut microbiota: An emerging driver influencing the immune system homeostasis and gastric carcinogenesis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022 Aug 15;12:953718

10 Baume P. An appreciation. In Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales 2021 Jun 1 (Vol. 154, No. 481/482, pp. 47-48). Sydney: Royal Society of New South Wales.

11 The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2005. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. Tues. 30 Apr 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/2005/7693-the-nobel-prize-in-physiology-or-medicine-2005-2005-6/

12 Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Weaver A, DiMagno EP, Carpenter HA, Perez-Perez GI, Blaser MJ. Gastric adenocarcinoma and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991 Dec 4;83(23):1734-9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.23.1734. PMID: 1770552.

13 Gregory AT. Jewels in the crown: The Medical Journal of Australia's 10 most‐cited articles. Medical journal of Australia. 2004 Jul;181(1):9-12.

14 Eslick GD, Tilden D, Arora N, Torres M, Clancy RL. Clinical and economic impact of “triple therapy” for Helicobacter pylori eradication on peptic ulcer disease in Australia. Helicobacter. 2020 Dec;25(6):e12751.

15 Global Cancer Observatory. International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization. Cancer Today. Updated April 15, 2025. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/en

16 This work includes that undertaken by Professor Richard Ferrero and Professor Brendan Jenkins at Monash University, Professor Phillip Sutton at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, and Dr Natalia Castano Rodriguez at UNSW.