NHMRC-supported research at St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research (SVI) has led to the development of bone cell biology as a field, defining the key bone cell types, their regulation, and interactions. This foundational work has had significant positive effects upon clinical practice, particularly in the treatment of osteoporosis, hypercalcaemia of malignancy, and osteogenic sarcoma. The research has contributed to the development of widely used therapeutics such as denosumab and has influenced global clinical practice.

- Video transcript

00:08.4 Thomas John Martin

My name is Thomas John Martin, known as Jack, and I'm Emeritus Professor, University of Melbourne, and I was director of St. Vincent's Institute of Medical Research until just over 20 years ago.00:23.6 Thomas John Martin

And I now am here on a retired basis. I just come in every now and then and pay attention to what my former colleagues continue to do. I suppose the first thing that influenced me to turn to an interest in bone was when, a few years after graduating in medicine, I just completed a physician's qualification.00:52.3 Thomas John Martin

I went to London and I met up with Iain Macintyre, who just discovered calcitonin, a hormone which influenced bone. And I was able to work with him on it and we produced some things together and it gave me an interest in bone that led to all the other things that I followed up with over the next years.01:17.0 Thomas John Martin

And then I came back to Melbourne and I was again fortunate to work with a mentor named Roger Mellick, who had done a lot of work on the other main hormone of bone, parathyroid hormone. And I worked with him for several years, during which I became interested in the cells of bone.01:38.7 Thomas John Martin

And at that stage, it wasn't really known clearly, that bone had anything as complicated as cells in it, but we started to be interested in those, and they were two of the main things that happened to me in the early years. And then I subsequently developed methods of looking in detail at the cells of bone, what they did, how they communicated with each other.02:05.7 Thomas John Martin

And that has occupied my life for much of the last 40 or 50 years.02:15.9 Thomas John Martin

At a stage when it was not really possible to isolate cells of bone. There was a bone tumour, a cancer bone, which we knew about, called the osteogenic sarcoma, the osteosarcoma.02:34.6 Thomas John Martin

It was a tumour of cells that formed bone. And there had just been developed a way of inducing that tumour in the rat by giving repeated injections of radioactive phosphorus.02:52.7 Thomas John Martin

So I did that while I was in Melbourne, working at the Royal Melbourne Hospital first, and then at the Austin Hospital. And I induced this osteogenic sarcoma in the rat and was able to isolate the cells from it. And these cells made a substance like bone, and they were very responsive to the hormone, parathyroid hormone.03:19.2 Thomas John Martin

So he used those in the study of the actions of parathyroid hormone and used them for many years. And from that we developed a what we call a clonal line of those cells, which we made available eventually all around the world.03:35.2 Thomas John Martin

And it's been used in hundreds of studies around the world and publications since that time, since the 70s and 80s. And one of the things that I noticed about that was that the ways in which parathyroid hormone acted upon it were very similar to what you'd expect of how parathyroid hormone would act upon the cells that formed bone, the so called osteoblasts.04:06.6 Thomas John Martin

And the osteoblasts were one of the two main, one of the three main cells of bone, the other cells of bone, the osteoclasts, continually break bone down. And they were thought to have entirely different origins, the osteoblast and the osteoclast.04:26.1 Thomas John Martin

But what we found was that the osteoblasts, beginning with the osteosarcoma cells, but then with the osteoblasts that were soon able to grow from burn, had a responsiveness to parathyroid hormone and to other substances that very closely resembled the responses of bone breakdown to those substances.04:51.2 Thomas John Martin

And so we developed the... I developed with a colleague in the United States, Gideon Rodan, who's since died, that there was a communication between the bone forming cells, the osteoblasts, and the bone breakdown cells, the osteoclasts, and that when certain substances, notably parathyroid hormone, acted upon the osteoblasts, that activities were generated that promoted the formation and activity of osteoclasts.05:27.8 Thomas John Martin

And that was a completely new hypothesis. It created a lot of interest and a lot of opposition at first, but we and others developed methods of showing that it was pretty well true that the formation activity of osteoclasts were governed by activities that were generated from cells of the osteoblast lineage.05:54.4 Thomas John Martin

This proved to be a very valuable hypothesis because we generated it in the early 1980s. And over the next 15 years, efforts, many efforts were made, including by us, to find what it is that the cells of the osteoblast lineage produced that generated the activity of osteoclasts.06:19.6 Thomas John Martin

And eventually, by the late 1980s, we weren't successful in finding what the substance was, but it a couple of pharmaceutical companies did. And it was a substance called RANK ligand, which was made by the osteoblast and which acted to promote osteoclast formation.06:45.8 Thomas John Martin

And if you inhibited this RANK ligand, you stopped the breakdown of bone. And that indeed was the basis of the development subsequently, since the late 1990s, of a drug which is an antibody to RANK ligand, which prevented the breakdown of bone and which has been used in the treatment of osteoporosis for that reason, osteoporosis, the bone loss that's common amongst particularly amongst elderly or women post menopause is due to the loss of bone.07:23.6 Thomas John Martin

And it's predominantly due to the overproduction and overactivity of these cells that break bone down, the osteoclasts. Well, this drug, which was based on the hypothesis that we developed, was established then and is still07:45.9 Thomas John Martin

the most marketed drug for the treatment of osteoporosis in the world. That's called Denosumab, that's sold in Australia as Prolia. So that was one major aspect of our work. But in the course of those years when we were trying to, trying to work out how the osteoblast controlled osteoclast function, we became very interested and produced a lot of work, which is fairly fundamental work on how the osteoblasts change during development and, and how the osteoclasts change during development and how the cells of bone communicate with each other.08:27.7 Thomas John Martin

And communication between the cells of bone is very important. And it takes place not only by this RANK ligand that I mentioned, but also by other short acting proteins which we call cytokines, which are produced by virtually all cells and which communicate, which mediate the communication between the cells of bone that had an effect on osteoporosis.09:01.3 Thomas John Martin

But over those years, when I came back to Melbourne from where I went to work in Sheffield, I came back and worked at the Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital, which was where we looked after old soldiers of the First and Second World War.09:17.6 Thomas John Martin

And very common amongst those soldiers was lung cancer. Many of them were smokers. And that lung cancer was often associated with a high blood calcium, the calcium having been leached out of bones. And I developed quite an interest in this complication of lung cancer, this high blood calcium.09:42.8 Thomas John Martin

And I worked on it for quite some years. And for quite a long time it was thought that those cancers inappropriately produced parathyroid hormone. And so we worked on what that substance was.09:59.0 Thomas John Martin

And eventually I found out that a cancer that we'd worked on in Sheffield before I came back to Melbourne produced an activity which resembled very closely what we would expect of such an activity from lung cancers.10:19.7 Thomas John Martin

And it was very like the activity of parathyroid hormone. So we set about trying to purify it from this lung cancer cell line. The lung cancer cell line was induced originally from a patient with this hypercalcemia of cancer of lung cancer.10:40.5 Thomas John Martin

And the protein that it produced, it took us quite some years, it took us about six years. But eventually, together with my colleague Richard Wettenhall, who was Professor of Biochemistry at La Trobe University, and my close working colleagues, Jane Moseley and Bruce Kemp, we purified this protein and Dick Wettenhall determined the sequence and it was similar to parathyroid hormone, but it differed.11:13.9 Thomas John Martin

It was similar to parathyroid hormone in the first part of it, the first tenth of it and the rest of it was quite different, but it was produced by this lung cancer and that was the cause of this hypercalcemia of malignancy.11:32.2 Thomas John Martin

And how it acted was it got generally into the circulation, it worked as a hormone, and it acted generally on the skeleton like parathyroid hormone to promote the activity of osteoclasts and their resorption and the tumour cells themselves that produced this substance, which we called parathyroid hormone related protein, or pdhrp, the tumour.12:02.9 Thomas John Martin

When the tumour spread to bone, when it metastasized to bone, it spread in bone by producing this substance locally. So it stimulated local breakdown of bone and allowed the tumour to, to establish and become established and growth as metastases in bone.12:20.5 Thomas John Martin

So that work had a major effect on thoughts about how is it that tumour cells grow as metastases in bone. Bone is a very hard substance. It's not a friendly location for cells to find themselves into.12:37.6 Thomas John Martin

But when cells get into the bone that produce this substance, PTHrP, they can produce it and resorb bone and allow a niche to be established so that the metastases can grow. And so we worked on that.12:55.3 Thomas John Martin

That was discovered in the mid-1990s and we worked on it and we've worked on it ever since. I stopped working a couple of years ago, but we've continued to work on it ever since, in addition to working, working on how the cells of bone communicate with each other.13:15.2 Thomas John Martin

And this substance was produced by cancers. But we also found that it has local effects in skin. It aids in the differentiation of the cells of skin.13:32.2 Thomas John Martin

It acts on the placenta to promote the movement of calcium across the placenta from mother, from the mother to the baby to make the calcium available for bone to mineralize and grow hard.13:49.8 Thomas John Martin

And there are many other effects also in normal tissues of this PTH related protein that we discovered in cancer. So it's not just a cancer hormone, but that was a major effect. That was a major outcome, a major clinical outcome, if you like.14:06.7 Thomas John Martin

Well, in the very early stage of my work, it was funded by the nhmrc. I had a fellowship when I came back from London with Macintyre. I had a fellowship to work with Roger Mellick for many years.14:21.8 Thomas John Martin

And then I was appointed by the University of Melbourne out at the Austin Hospital and obtained project grants from the NHMRC and from what was then the Anti Cancer Council of Victoria. And the Anti Cancer Council supported our research with project grants for quite some years.14:41.6 Thomas John Martin

And so too did the NHMRC. And beginning in 1984, we developed a programme grant with the NHMRC as a major grant, five year grant that we obtained successively over the next 25 years.15:02.2 Thomas John Martin

So for 25 years, until 2009, I had a programme grant from the NHMRC which helped us to appoint the colleagues that worked with me many times over those years. When I did medicine, I decided that I wanted to know the biochemical mechanisms of disease.15:25.9 Thomas John Martin

What went wrong with biochemistry that caused diseases? And there were plenty of examples that we didn't. We didn't have any idea what the biochemical mechanisms were. And when I graduated, I still wanted to understand the biochemical mechanisms of disease.15:45.7 Thomas John Martin

And when I was a resident at this hospital, I took a year as the resident of a man named John Owen, who was a Scot, who was in charge of the biochemistry department here at the hospital. And I worked with him and that gave me the impetus to continue to work in biochemical mechanisms.16:10.2 Thomas John Martin

At that stage I had also an appointment in the University of Melbourne biochemistry department, teaching biochemistry to medical students. And that inspired me further to want to know, what did all this mean? What did it mean to understand a bit about biochemistry?16:27.0 Thomas John Martin

How did that apply to any diseases? And so it was that which drove me and I happened to choose bone because that was what I was exposed to early on. And that's what I found extraordinarily interesting. Well, in the early days, so little was known about bone that once I realised that there were cells of bone, I just wanted to know the truth.16:49.4 Thomas John Martin

How were those cells governed? How did hormones act upon them? That was my starting point. How did hormones act upon the cells of bone? And then as time went on and I eventually realised that what we did was relevant to, at first osteoporosis and then cancer.17:10.2 Thomas John Martin

I really wanted to know how the control of these cells. Are bone related to osteoporosis and wanted to know and to cancer? Well, some of my interests outside of work I can't really follow particularly well anymore.17:29.6 Thomas John Martin

I was very interested in fly fishing and got to be reasonably good at it. I played a lot of golf. I can't really play golf anymore. I played cricket. I was interested in cricket. I'm still very interested in cricket and in golf.17:46.3 Thomas John Martin

I'm interested also in football. And I'm interested in my family and my grandchildren, of which I have a large number. And so but I don't have any hobbies like woodwork or gardening. I can't stand gardening.18:02.1 Thomas John Martin

And and so I read a lot. I'm very interested in music, particularly classical music. But I lead the life of an elderly person. And I come into work. When I say work, it's not really work for me anymore.18:18.0 Thomas John Martin

I come in a couple of days of work because I continue to be interested in the ways in which my colleague, Natalie Sims, continues and develops further interests in how the cells of bone communicate with each other and how they work.18:35.7 Thomas John Martin

And this is an extension of her work that she did with us for many years, but which goes beyond anything that I ever had any direct involvement in. But I find it extremely interesting and interesting enough for me to keep coming in here while I can.00:08.4 Thomas John Martin

My name is Thomas John Martin, known as Jack, and I'm Emeritus Professor, University of Melbourne, and I was director of St. Vincent's Institute of Medical Research until just over 20 years ago.End of transcript

Origin

Humans are born with 270 bones which during development fuse to create an adult skeleton comprised of 206 bones.1 These bones are dynamic, growing and changing over our lifespan. The changing nature of bones with age presents problems such as osteoporosis, a condition where bones are weak and prone to fracture, defined clinically by a low bone mineral density scan.

Age-related osteoporosis is caused by new bone generation not keeping pace with bone breakdown. In 2022, around 3.4% of the Australian population (853,600 people) was estimated to be living with osteoporosis or low bone mineral density.2 However, the prevalence is likely higher as it often remains undiagnosed until a fracture occurs. The disease disproportionately affects older individuals and women and has increased in prevalence since 2001.

Individuals with osteoporosis are particularly predisposed to trauma fractures, which occur from a fall or impact that would not normally cause a bone to break in a healthy person. Such fractures remain a major cause of morbidity in Australia, affecting one in two women and one in four men over the age of 60 years.3 Mortality is increased after all minimal trauma fractures, even when these fractures are minor. Hip fractures are particularly devastating, leading to decreased quality of life, increased mortality and loss of functional independence.

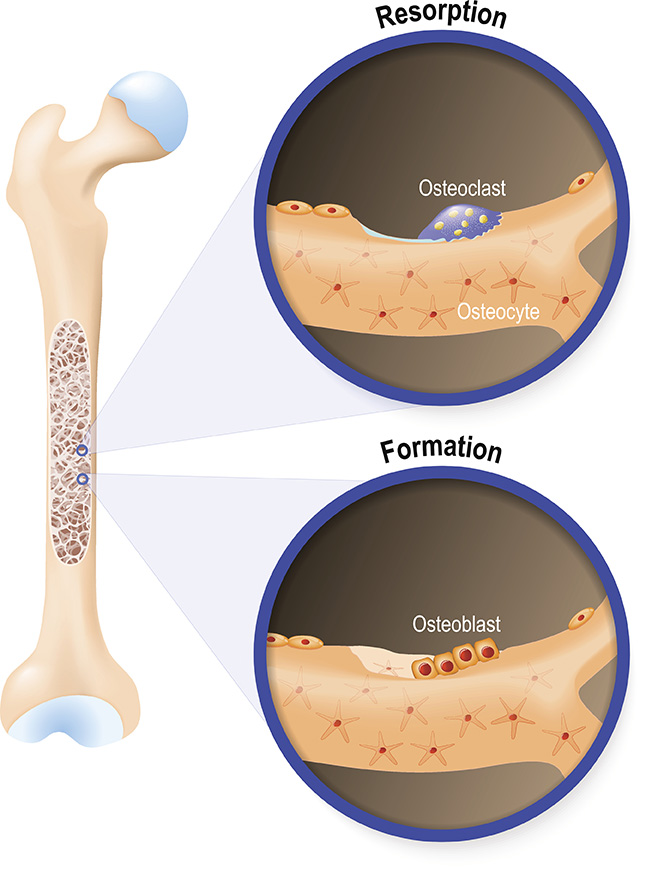

Bone structure is maintained primarily by three key cell types: osteoblasts, which build new bone; osteoclasts, which break down old bone; and osteocytes, which help regulate bone maintenance and mineral balance. These three cell types were first described in the 19th and early 20th centuries, leading bone to be considered as a ‘living tissue’, however these cellular components remained poorly understood because of the inability of researchers to isolate the cells. This was until NHMRC funded researcher Thomas ‘Jack’ Martin and colleagues at the University of Melbourne turned to studying a tumour to solve this problem.

Investment

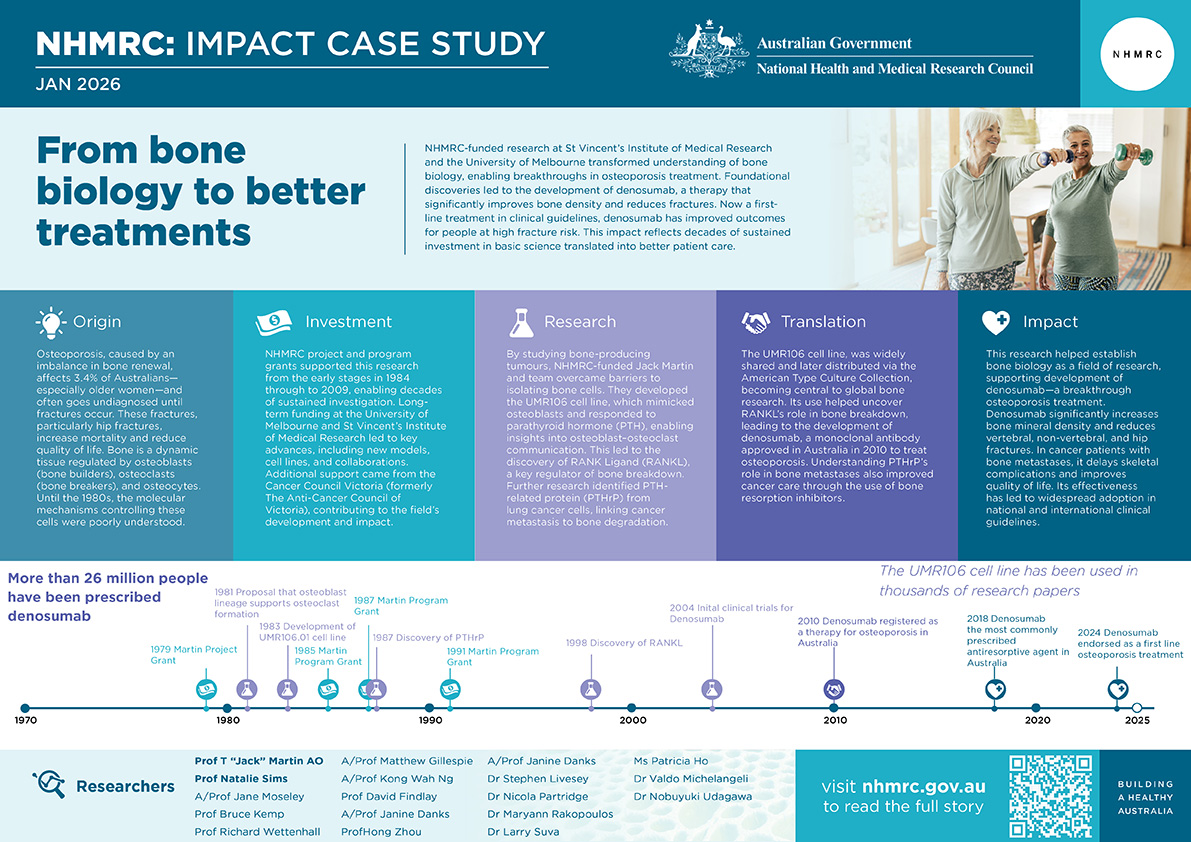

The research of Martin and his colleagues was initially supported by NHMRC Project Grants and subsequently received multiple NHMRC Program Grant support from 1984 to 2009. Additional NHMRC Project Grants followed, enabling sustained investigation over decades. The long-term investment for researchers working in the University of Melbourne and SVI facilitated the development of new models, cell lines, and collaborations that were critical to the field’s advancement.

Research was also supported by project grants from the Cancer Council Victoria (then known as The Anti-Cancer Council of Victoria).

The PDF poster version of this case study includes a graphical timeline showing NHMRC grants provided and other events described in the case study.

Research

Using radioactive phosphorous (P32), Martin and colleagues were able to induce a tumour in the femur (the thigh bone) of a rat. This tumour – called an osteogenic sarcoma – was made up of cells that produced bone. The bone cells produced by these sarcomas were able to be isolated and were found to be very responsive to the hormone parathyroid hormone (PTH).4 From these cells, researchers in collaboration with Dr Ray Bradley were able to develop the UMR106 cell line 5, 6 which behaved similarly to what would be expected of osteoblasts 6, 7, 8, 9

These cells enabled further study of the communication between osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Researchers found that when certain substances acted on osteoblasts (eg PTH and prostaglandins), this regulated the activity and formation of osteoclasts. This led to the hypothesis that the formation and activity of osteoclasts are determined by activity produced by osteoblasts.10, 11 The chemical responsible for these interactions was identified in the late 1990s as RANK Ligand (RANKL).12, 13 This molecule was made by osteoblasts and promoted the formation of osteoclasts and when its actions were inhibited, bone breakdown was stopped.14

Researchers went on to investigate other proteins that facilitated communication between bone cells. Here they looked to lung cancer which can be associated with high levels of blood calcium (hypercalcemia) as calcium is leeched from the bones. Using a cell line from a lung cancer patient they isolated a protein similar to PTH which was produced by these cancer cells and acted on bones.16, 17, 18, 19 This protein, which they called PTH related protein (PTHrP) increased osteoclast formation and activity, facilitating increased bone breakdown. When produced by cells locally in bone marrow, it facilitated the growth of cancer metastases in the bone itself by promoting bone breakdown, explaining how these cancers can grow in what would otherwise be thought of as a hard tissue that would be a poor supporter of cell growth.19

PTHrP was also found to be produced in many other tissues, where various physiological effects were exerted. These included actions on the placenta to allow calcium to be provided to the foetus, and upon smooth muscle cells of the vasculature to relax blood vessels.20, 21

Translation

The UMR106 cell line isolated from osteogenic sarcoma was from the outset made available to scientists who had reasons to study the cells. In the late 1980s, for convenience, the UMR106 cells were given to the American Type Culture Collection, a cell repository for the distribution of cell lines. Since that time, the UMR106 cells have become a fundamental research tool internationally and have been referred to within thousands of publications.

The discovery of how RANKL stimulated osteoclast activity and increased bone breakdown led to the development of a drug by Amgen against this target and an effective treatment for osteoporosis. This monoclonal antibody therapy (Denosumab) acts by binding to RANKL produced by osteoblasts rendering it unable to promote the development of osteoclasts, reducing the breakdown of bone by these cells. Denosumab was first registered for the treatment of osteoporosis in Australia in 2010.22 In a review of 27 studies of osteoporosis treated worldwide, it was concluded that Denosumab was a cost effective and dominant option when compared with oral bisphosphonate therapy.23

PTHrP expression in breast cancer was linked to improved survival, suggesting its use as a prognostic marker and potential tumour suppressor. Understanding PTHrP’s role in bone metastases informed the use of bone resorption inhibitors in cancer patient19, improving management of skeletal complications.

Outcomes and impacts

The UMR106 osteoblast cell line played a significant role in the establishment of the field of bone biology. These cells have been adopted widely and used in more than 400 peer-reviewed publications in bone biology, cancer, and pharmacology.

Targeted therapies such as denosumab and emerging anti-PTHrP agents have improved treatment options for osteoporosis and cancer-related bone disease, transforming patient outcomes. Denosumab significantly reduces the decline in bone mineral density and reduces vertebral, non-vertebral, and hip fractures in people with osteoporosis, while in cancer patients with bone metastases, it delays skeletal-related events, lowers fracture risk, and improves quality of life compared to bisphosphonates (a class of drugs used for osteoporosis treatment).24, 25, 26 In Australia, more than one million prescriptions for denosumab were dispensed between 2023 and 2024.27 Globally, over 26 million people are estimated to have received treatment with denosumab.28

Research on RANKL inhibition and denosumab has been fully integrated into national osteoporosis clinical guidelines shaping recommendations for clinical practice. In 2024, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and Healthy Bones Australia endorsed denosumab as a first-line option for postmenopausal women at high fracture risk and as an alternative to bisphosphonates for men at increased risk.29 International guidelines including the UK National Osteoporosis Guideline Group, International Osteoporosis Foundation and Endocrine Society guidelines recognise denosumab as an effective antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis, particularly in patients at high or very high fracture risk.

However, all guidelines place emphasis on continuity of therapy. Treatment should not be stopped or delayed without specialist advice, and if discontinued, transition to another antiresorptive agent is required to prevent rebound fractures.

Researchers

Professor T John Martin AO

Jack Martin studied medicine at the University of Melbourne (UoM), graduating in 1960. After holding a position as Professor of Chemical Pathology at the University of Sheffield, UK, he returned to the University of Melbourne as Foundation Professor of Medicine at the Heidelberg and Repatriation General Hospital. He then became Director of SVI in 1988, holding the position until 2002. He was instrumental in establishing SVI as a leading centre for bone and cancer research. Martin was elected Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science in 1998. He was appointed Officer of the Order of Australia in 1996 for his contributions to medical research, particularly in bone biology and cancer, and was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society (London) in 2000. He was named 2013 Victorian Senior Australian of the year.

Professor Natalie Sims

Natalie Sims received her PhD from the University of Adelaide in 1994. She joined SVI in 2006 before becoming Associate Director (2009) then Deputy Director of SVI in 2018. She has held editorial roles in journals including Bone, Journal of Biological Chemistry, Journal of Bone and Mineral Research and Endocrine Reviews. She has received multiple awards for her work including the Paula Stern Achievement Award (2020), Herbert A Fleisch Award (2013) and Fuller-Albright Award (2010).

Other researchers

Other researchers that contributed to the impacts described in this case study include, Associate Professor Jane Moseley, Professor Bruce Kemp, Professor Richard Wettenhall, Associate Professor Matthew Gillespie, Associate Professor Kong Wah Ng, Professor David Findlay, Associate Professor Janine Danks, Professor Hong Zhou, Dr Stephen Livesey, Dr Nicola Partridge, Dr Maryann Rakopoulos, Dr Larry Suva, Ms Patricia Ho, Dr Valdo Michelangeli and Dr Nobuyuki Udagawa.

Partner

This case study was developed in partnership with St Vincent’s Institute of Medical Research.

Under NHMRC’s Funding Agreement, Administering Institutions must comply, and require their Participating Institutions, Research Activities and applications to comply, with relevant legislation. At the time of writing, relevant legislation governing the use of animals for research includes state and territory animal welfare legislation. NHMRC also requires compliance with NHMRC approved Standards and Guidelines and any applicable NHMRC policies. At the time of writing, and with respect to animals, these include the:

- Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (2018)

- Australian code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes 8th edition (2013, updated 2021)

- Best practice methodology in the use of animals for scientific purposes (2017).

- Principles and guidelines on the care and use of non-human primates for scientific purposes (2016)

- A guide to the care and use of Australian native mammals in research and teaching (2014).

Ethical, scientific, veterinary and medical standards and practices related to animal research change over time. NHMRC-funded research activities that occurred before the present time were subject to the legislation and NHMRC’s Standards, Guidelines and policies in force at the time that they occurred.

References

The information and images from which impact case studies are produced may be obtained from a number of sources including our case study partner, NHMRC’s internal records and publicly available materials. Key sources of information consulted for this case study include:

1Marshall Cavendish Corporation. Mammal anatomy: an illustrated guide. New York: Marshall Cavendish; 2010. p. 129. ISBN: 9780761478829

2Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 2]. Available from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoporosis

3Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, et al. Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 2007; 22: 781-788.

4Martin TJ, Ingleton PM, Underwood JC, Michelangeli VP, Hunt NH, Melick RA. Parathyroid hormone-responsive adenylate cyclase in induced transplantable osteogenic rat sarcoma. Nature 1976; 260(5550): 436-8.

5Partridge NC, Frampton RJ, Eisman JA, et al. Receptors for 1,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 enriched in cloned osteoblast-like rat osteogenic sarcoma cells. FEBS Lett 1980; 115(1): 139-42.

6Partridge NC, Alcorn D, Michelangeli VP, Ryan G, Martin TJ. Morphological and biochemical characterization of four clonal osteogenic sarcoma cell lines of rat origin. Cancer Res 1983; 43(9): 4308-14.

7Partridge NC, Kemp BE, Veroni MC, Martin TJ. Activation of adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase in normal and malignant bone cells by parathyroid hormone, prostaglandin E2, and prostacyclin. Endocrinology 1981; 108(1): 220-5.

8 Partridge NC, Kemp BE, Livesey SA, Martin TJ. Activity ratio measurements reflect intracellular activation of adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase in osteoblasts. Endocrinology 1982; 111(1): 178-83.

9Livesey SA, Kemp BE, Re CA, Partridge NC, Martin TJ. Selective hormonal activation of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase isoenzymes in normal and malignant osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 1982; 257(24): 14983-7.

10Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Role of osteoblasts in hormonal control of bone resorption--a hypothesis. Calcif Tissue Int 1981; 33(4): 349-51.

11Martin TJ. Drug and hormone effects on calcium release from bone. Pharmacol Ther 1983; 21(2): 209-28.

12Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, et al. Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 1998; 93(2): 165-76.

13Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, et al. Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95(7): 3597-602.

14Seeman E, Martin TJ. Antiresorptive and anabolic agents in the prevention and reversal of bone fragility. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2019; 15(4): 225-36.

15Melick RA, Martin TJ, Hicks JD. Parathyroid hormone production and malignancy. Br Med J 1972; 2(5807): 204-5.

16Moseley JM, Kubota M, Diefenbach-Jagger H, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein purified from a human lung cancer cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987; 84(14): 5048-52.

17Suva LJ, Winslow GA, Wettenhall RE, et al. A parathyroid hormone-related protein implicated in malignant hypercalcemia: cloning and expression. Science 1987; 237(4817): 893-6.

18Kemp BE, Moseley JM, Rodda CP, et al. Parathyroid hormone-related protein of malignancy: active synthetic fragments. Science 1987; 238(4833): 1568-70.

19Powell GJ, Southby J, Danks JA, et al. Localization of parathyroid hormone-related protein in breast cancer metastases: increased incidence in bone compared with other sites. Cancer Res 1991; 51(11): 3059-61.

20Rodda CP, Kubota M, Heath JA, et al. Evidence for a novel parathyroid hormone-related protein in fetal lamb parathyroid glands and sheep placenta: comparisons with a similar protein implicated in humoral hypercalcaemia of malignancy. The Journal of endocrinology 1988; 117(2): 261-71.

21 Kovacs CS, Manley NR, Moseley JM, Martin TJ, Kronenberg HM. Fetal parathyroids are not required to maintain placental calcium transport. J Clin Invest 2001; 107(8): 1007-15.

22The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Denosumab. In: Osteoporosis: Pharmacologic approaches to prevention and treatment. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP; 2024 [cited 2025 Jul 4]. Available from: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/osteoporosis/pharmacologic-approaches-to-prevention/denosumab

23Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, Pinto D, Si L, Kremer I, Bours S, de Bot R, Boonen A, Evers S, van den Bergh J, Reginster JY, Hiligsmann M. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021 Feb;39(2):181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9. PMID: 33026634; PMCID: PMC7867562.

24Bone HG, et al. Ten years of denosumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the FREEDOM extension trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32(3):448-455. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30138-9

25Ha J, Lee YJ, Kim J, Jeong C, Lim Y, Lee J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of denosumab: insights beyond 10 years of use. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2025;40(1):47-56. doi:10.3803/EnM.2024.2125.

26Lu J, Hu D, Zhang Y, Ma C, Shen L, Shuai B. Current comprehensive understanding of denosumab (the RANKL neutralizing antibody) in the treatment of bone metastasis of malignant tumors, including pharmacological mechanism and clinical trials. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1133828. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1133828.

27Top 10 drugs 2023–24. Aust Prescr. 2024;47(6):194. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2024.048. Available from: https://australianprescriber.tg.org.au/articles/top-10-drugs-2023%E2%80%9324.html

28Prolia® (denosumab). Postmenopausal osteoporosis [Internet]. Thousand Oaks (CA): Amgen Inc.; [cited 2025 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.prolia.com/taking-prolia/postmenopausal-osteoporosis

29The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and Healthy Bones Australia.

Osteoporosis management and fracture prevention in postmenopausal women and men over 50 years of age. 3rd ed. East Melbourne, Vic: RACGP; 2024. Available from: https://healthybonesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/hba-racgp-guidelines-2024.pdf