Skin sores and infections are worldwide problems but are particularly important health issues for remote-living Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in Australia. Rates of skin disease have been high in such communities for decades: not just by Australian urban standards but by world standards. With one study finding impetigo prevalence as high as 70%,1 these problems are so prevalent that they have come to be considered ‘normal’ – by children, their families and even by health care providers. NHMRC-funded researchers at the Menzies School for Health Research (Menzies) and The Kids Research Institute have made major contributions to improving skin health in these communities.

Origin

Intact skin is usually resistant to infection, however when skin is disrupted – by abrasions, eczema, attack by parasitic creatures (e.g. mites, mosquitos, head lice) or fungi (e.g. tinea) – this can in turn lead to bacterial infection. Sores infected with Staphylococcus aureus (Golden staph) and/or Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Strep or GAS) are called ‘impetigo’ and are a particular problem for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Skin sores and infections are not just unsightly and painful, but they can impair individual wellbeing, growth and educational development (e.g. through missed school days). If left untreated, infected skin sores can potentially lead to subsequent systemic infections and life-threatening problems such as sepsis, chronic renal disease and rheumatic heart disease.

Scabies

Scabies is a contagious human skin infestation by the tiny mite Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis. The word ‘scabies’ comes from the Latin word scabere which means ‘to scratch'. The scabies mite burrows into the skin, leaving behind tiny scybala (faecal droppings) that cause severe itchiness and a pimple-like rash. Scratching may cause skin breakdown and an additional bacterial infection in the skin, causing impetigo.

Skin pathogens are highly transmissible, both through skin-to-skin contact and contact with infected objects or material such as bedclothes. When people do not live in safe and healthy conditions – when they do not have access to high quality housing, power supplies, sanitation and waste management, food or water, pest or mosquito control, community education and health care – then chronic and serious skin infections and their consequences may become endemic within their community.

Rates of skin diseases have been high in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander remote communities for decades. Not just by Australian urban standards but by world standards. With one study finding impetigo prevalence as high as 70%,1 these problems are so prevalent that they have come to be considered ‘normal’ – by children, their families and even by health care providers.2 However, researchers at Menzies in Darwin and The Kids Research Institute at University of Western Australia (UWA) have engaged in long-term programs to improve skin health in these remote communities.

Investment

Over time, NHMRC has funded a range of researchers at Menzies as well as at The Kids Research Institute, and the University of Melbourne, to support research into improving skin health. These researchers include: Asha Bowen, Bart Currie, Jonathan Carapetis, Steven Tong, Shelley Walton, David Kemp, Deborah Holt, Ross Andrews, Kerry Gaudry, Elizabeth McDonald and Therese Kearns. Significant long-term support for research into skin health has also been provided by the Australian Government’s Cooperative Research Centres program to (what is now) the Lowitja Institute. Other funding sources include the Medical Research Future Fund, the WA Department of Health, Healthway, Rio Tinto Aboriginal Foundation and The Ian Potter Foundation.

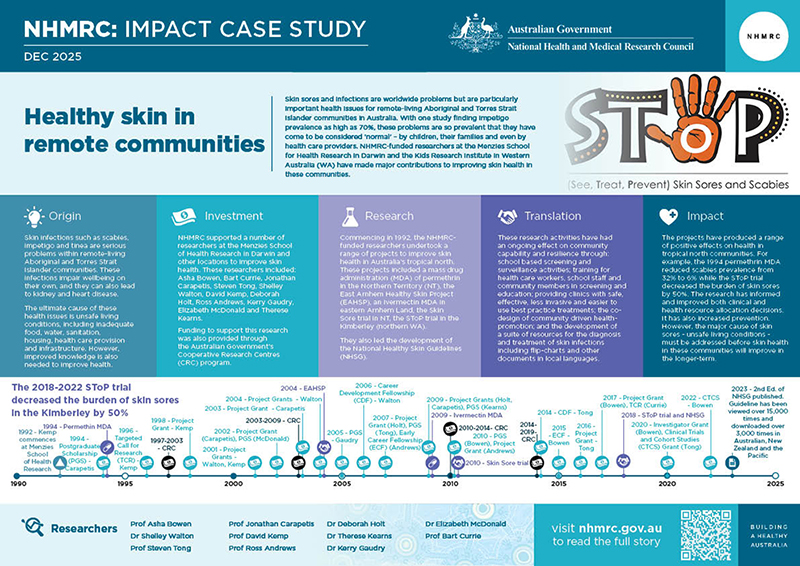

The PDF poster version of this case study includes a graphical timeline showing NHMRC grants provided and other events described in the case study.

Research

In 1992, when David Kemp became Deputy Director at Menzies, he and colleagues Shelly Walton and Bart Currie embarked on new studies attempting to improve skin health in the Northern Territory. Using molecular fingerprinting, their research showed that – contrary to what had been believed – human scabies mites were different from those infesting dogs in scabies endemic communities. As a consequence, treatment resources were shifted away from dog management and towards humans.

In 1994, as part of his PhD research, Jonathan Carapetis assessed the use of permethrin (a medical insecticide) in a mass drug administration (MDA) trial in a remote island Aboriginal community of the Northern Territory. In addition to the population MDA, scabies cases and contacts were also treated with topical permethrin and impetigo cases were treated with an antibiotic (intramuscular benzathine penicillin G or BPG). Scabies prevalence at 25 months fell from 32% to 6%.

In 1997, the first of a series of CRCs commenced with a focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. In 2004, the (then) CRC for Aboriginal Health released the Healthy Skin Program Statement which recognised a central role for understanding and improving the social determinants of health when seeking to improve community skin health.

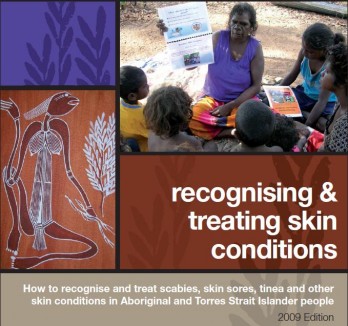

This work led to the Healthy Skin Program which brought together scientists, epidemiologists, community awareness and nurse education of communities as part of an integrated effort to tackle scabies and related infections. Biomedical research was complemented by audience appropriate information packages, such as flip-charts for skin infection recognition and treatment, that were distributed to affected communities. The program also led to the later development of the National Healthy Skin Guidelines.

A number of major research projects were conducted to improve skin health in remote communities as part of or in collaboration with the Healthy Skin Program.

East Arnhem Healthy Skin Project (EAHSP)

From 2004 to 2007, and led by Ross Andrews and Therese Kearns, the EAHSP aimed to reduce the prevalence of scabies, skin sores and tinea in remote Aboriginal communities within the East Arnhem region. The project’s activities included annual mass community scabies treatment days and routine screening and treatment of skin infections. It also used a suite of resources for the diagnosis and treatment of skin conditions, including radio programs and flip-charts in local languages, and included the formal training of 11 community health care workers.

The project team made 99 visits to participating communities, conducted 6,038 skin assessments for 2,329 children aged less than fifteen years (88% of the target population group) and conducted a further 624 follow-up visits.

As a result of the project, community workers became more involved with screening and education in baby clinics as well as continuing the work in the community. Skin sore prevalence reduced substantially over the three-year study period from 46% in the first 18 months to 28% in the last 18 months. Scabies prevalence remained constant over the three-year study period at 14%, however those individuals who did not acquire scabies were almost 6 times more likely to belong to a household where everyone in the house had used the scabies treatment cream.

The study was the first to monitor tinea prevalence over time in Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory, finding an average monthly prevalence of 15%.3

Ivermectin MDA

Also in 2009, Terese Kearns led an MDA trial for scabies in eastern Arnhem Land. Participants were administered a single ivermectin dose, repeated after 2–3 weeks if scabies was diagnosed. The trial involved over 1,000 participants at each population census. Scabies prevalence fell from 4% at baseline to 1% at month 6. At month 18, scabies prevalence was 2%.

Skin Sore Trial

Starting in 2010, and as part of her PhD research, Asha Bowen trialled a new approach to skin infection control. The trial was conducted because the standard approach being used in the Northern Territory was intramuscular injection of BPG. Such injections are extremely painful to receive, sometimes difficult to obtain and of decreasing efficacy due to antibiotic resistant forms of bacteria. Consequently, only about 5% of children who needed treatment were receiving it.

The Skin Sore Trial showed that treatment with an alternative antibiotic (trimethoprim/ sulphamethoxazole or SXT), which is palatable, has excellent skin penetration and low resistance rates, was just as effective. The trial showed that dosing either twice a day for three days (six doses) or once a day for five days (five doses) was equally effective to a single injection of BPG. This made it possible for the doses to be provided at school and thereby increase uptake.

The data from the trial also confirmed that GAS is the inciting pathogen for impetigo, an important piece of evidence connecting skin health to the prevention of acute rheumatic fever (ARF - which is caused by GAS).

SToP trial

A major finding of previous trials was that sustained reductions in skin sore prevalence would not be achieved unless there was strong and ongoing community involvement in prevention.

The See, Treat, Prevent Skin Sores and Scabies (SToP) trial was a large randomised trial of skin health activities implemented between 2018 and 2022 in the Kimberley (the northern region of Western Australia). It was aimed at improving the awareness, detection and treatment of skin infections by incorporating sustainable community-level activity that could lead to ongoing reductions in infection. Rather than simply adding to knowledge about what works, the trial was intended to increase prevention.

Prevention was the key requirement of Aboriginal health partners (Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service and Nirrumbuk Environmental Health and Services), and their leadership informed SToP activities. These activities included school-based screening and surveillance activities, and training for health workers, school staff and community members. It also included providing community clinics with safe, effective, less invasive and easier to use best-practice treatments, the co-design and delivery of community-driven skin-related health promotion and environmental health resources.

The magnitude of the project was huge, involving 3,084 skin checks over four-years, with project members travelling over 45,000 kms to 9 communities and working with community, school staff and clinic staff members and other service providers. Acceptance and uptake of community activities was high, leading to a marked decrease in skin infection during the trial period.

The aim of the SToP trial was to decrease the burden of skin sores by 50 per cent. This goal was accomplished. While the rate of skin infections early in the study period was close to 40 per cent, this had been reduced to 20 per cent by the end of the trial.

The results demonstrated that improved detection through skin surveillance in schools played the biggest role in achieving reduced infection rates – having a strong focus on regular skin checks, communicating these results to the school, clinic and families, and elevating skin health as a priority were the key factors.

National Healthy Skin Guideline

Asha Bowen led the development of two editions of the National Healthy Skin Guideline. The first was released in 2018 and the second in 2023. The 2nd edition guideline was endorsed by 13 different healthcare and medical research organisations, included a strong focus on the social determinants of health, provided evidence for the effectiveness of control programs to reduce scabies, impetigo and head lice, and provided detailed guidance about how to treat these issues as well as tinea and eczema for remote and urban contexts.

Translation

Results of the Skin Sore Trial have been highly cited globally and have led to a revision of the 6th edition of the Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association (CARPA) manual, a well-utilised primary health care manual in the Northern Territory. The results have also been included in the national antibiotic reference source (Therapeutic Guidelines: Antibiotic) released in November 2014 and in treatment guidelines in the Kimberley. SXT now sits in regional, national and international guidelines as an effective treatment for impetigo, based on the results of the trial.

The SToP trial was transformational in terms of community ownership. It demonstrated that a community led partnership model was powerful in producing health benefits. The trial led to the development of hip hop videos (Gotta Keep it Strong and Hip Hop 2 SToP) and 8 community books in local languages using photos, local art work and local bush medicine. This was the first time that one of these languages had been written in a book.

Books, visual clinical handbooks and flip-charts developed as part of the Healthy Skin program have been translated into many languages both overseas and in Australia. Along with posters from the guidelines, they have been referenced in a large number of national guidelines overseas as a source of best practice and information.

The SToP Trial also brought attention to the importance of healthy homes and environmental health to prevent skin infections. Yarning with community members provided community perspectives on the importance of environmental health and the gaps in service provision that are continuously impacting good health.4

The National Healthy Skin Guideline has been widely viewed and downloaded, with over 15,000 views and over 3,000 downloads in Australia, NZ and the Pacific.

Outcomes and impacts

Health and medical research has an important role to play in improving skin health in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, and each of the projects described above has led to positive health benefits for the involved communities. Diagnosis and reporting of scabies and skin sore cases in these communities have improved during the last two decades.

That said, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children still have some of the highest rates of scabies and impetigo in the world and the overall situation is worsening rather than improving. 5 6 While the majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children live in major cities and regional areas, a greater proportion of these children live in remote and very remote areas compared with other Australian children. 7 8 Consequently, the social determinants of health are particularly important for these communities.

Comprehensive skin health programs supported by government policies, in partnership with schools and community empowerment to improve the social determinants of health are needed to achieve sustained improvements in skin health for these children and their families.

Researchers

Professor Asha Bowen OAM

Asha Clare Bowen completed a medical degree in 2004 at the University of Sydney and a PhD in 2014 at Menzies and Charles Darwin University. Bowen worked at Menzies (2010–2014) then joined the Telethon Kids Institute in 2015, where she leads the Healthy Skin and ARF Prevention program. In parallel, Bowen serves as a clinician at Perth Children’s Hospital. Bowen’s contributions to knowledge and health have been recognised through awards including the 2020 Eureka Prize for Emerging Leader in Science, the 2022 Australian Society of Infectious Diseases Frank Fenner Award, and an Order of Australia Medal (OAM) in 2024 for service to medicine in the field of clinical diseases.

Bowen was a General Paediatrician and Paediatric Infectious Diseases Specialist, Royal Darwin Hospital (2012-2014). From 2014 she was a Clinician in the Infectious Diseases Department, Perth Children's Hospital, and has been Head of Department since 2020. From 2014 Bowen was also Clinical Professor, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Paediatrics, University of Western Australia. In addition, she has been involved with the World Society for Pediatric Infectious Diseases as a Board Member (2019-2021), Vice President (2021-2023) and President (2023-2025).

Dr Shelley Walton

Shelley Walton completed a Bachelor of Applied Science in 1989 at the University of Central Queensland, and a PhD in 1998 at the University of Sydney focused on scabies parasite biology. Walton then joined the Menzies School of Health Research where she led the Skin Pathogens Research Laboratory. Walton’s work has led to the development of an immunodiagnostic test for scabies and contributed to scabies being added to the World Health Organisation list of Neglected Tropical Diseases in 2017.

Professor Steven Tong

Steven Tong completed a medical degree in 1998 at the University of Melbourne and a PhD in 2010 at Menzies and Charles Darwin University. He worked at Menzies Royal Darwin Hospital (2006–2012) during and after his PhD, then moved to Melbourne to join the Peter Doherty Institute in 2013. Tong was an inaugural NT Fulbright Scholar at Stanford University in the US. As co-head of Clinical Research at the Doherty Institute, Steven Tong leads large international trials to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. He remains a clinician at Royal Melbourne Hospital and an Honorary Fellow at Menzies.

Professor Jonathan Carapetis AM

Jonathan Rhys Carapetis, after completing a medical degree at the University of Melbourne (1986), completed postgraduate medical training at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and Royal Children’s Hospital (Melbourne; 1987-1992) and then a PhD at the University of Sydney (1999). Carapetis was a Theme Director at the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and Consultant in Paediatric Infectious Diseases at the Royal Children’s Hospital until 2006, when he became Director of Menzies (2006-2012). In 2012, Carapetis became Executive Director at the Telethon Kids Institute in Perth. In 2018, Carapetis was appointed a Member of the Order of Australia for significant service to medicine in the field of paediatrics, particularly the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of rheumatic heart disease.

Professor David Kemp OAM

David Kemp completed a Bachelor of Science (1969) and then a PhD (1973) at the University of Adelaide (1969). Kemp undertook research at CSIRO’s Division of Plant Industry (1975), then a fellowship at Stanford University (1976-1978). He worked at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne (1978-1992) and was Deputy Director of the Menzies School (1992-2000). He then took a role as head of a malaria & scabies laboratory at the Queensland Institute of Medical Research in Brisbane, where he worked until retiring in 2006. In 2008, Kemp was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to medical research as a molecular biologist, particularly in the areas of tropical health and infectious diseases, through contributions to Indigenous health and to professional organisations.

Professor Ross Andrews

Ross Andrews completed a Diploma of Applied Science (Environmental Health) at Swinburne University of Technology (1984), a Master of Public Health at Monash University (1995), a Master of Applied Epidemiology at the Australian National University (ANU - 1998) and then a PhD at ANU (2004). Prof. Andrews’ expertise comes from extensive field experience and advanced applied epidemiology training. In 2006, he joined the Menzies School of Health Research as an epidemiologist where he worked until 2021. He also served on the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (2008-2018), including a term as ATAGI Chair (2014–2017).

Dr Deborah Holt

Deborah Holt completed a Bachelor of Applied Science at Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (1992) then a PhD at the University of Sydney (2000). Her doctoral research, based in Darwin, focused on molecular microbiology. After completing her PhD, Holt continued at Menzies (2000 onward) as a molecular biologist and is now Honorary Senior Research Fellow at Menzies and a Senior Lecturer at Charles Darwin University.

Dr Thérèse Kearns

Thérèse Kearns graduated as a registered nurse (1989), a registered midwife (1991), completed a Master of Applied Epidemiology at ANU (2002) and a PhD at Charles Darwin University (through Menzies School of Health Research; 2014). Kearns worked for 15 years (1991–2006) in rural and remote Aboriginal communities across Western Australia and the Northern Territory as a community nurse and midwife. In 2006 she joined Menzies School of Health Research, where she serves as an Honorary Fellow in the Tropical Health Division.

Dr Kerry Gaudry

Kerry Catherine Gaudry completed a medical degree in 1993 and became a Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Paediatrics) in 2002. After residency, Gaudry served communities such as Yuendumu, Ti Tree, and Borroloola on a rotation basis. Since the mid-2010s, Dr. Gaudry has been closely associated with the Robinson River Community Health Centre (a very remote Gulf Country community), where she provides regular paediatric clinics.

Dr Christine Connors OAM

Christine Maree Connors completed a medical degree at Monash University (1983) and a Master of Public Health at the University of New South Wales (1996). She became a Public Health Medicine specialist in 1997. After moving to the Northern Territory, Connors became Program Director of the NT Preventable Chronic Disease Program. From 2013 to 2021, she served as General Manager of Primary Health Care for the Top End Health Service and in 2023, Dr. Connors was appointed Chief Health Officer of the Northern Territory. In 2019, Connors was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for service to medicine.

Professor Bart Currie

Bart Currie completed a medical degree at the University of Melbourne (1978), a Diploma of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene at the London School of Tropical Medicine (1985) and a PhD at Charles Darwin University (2022). Currie was Head of the Menzies Clinical Division and then Interim Director of Menzies from August 2005 to March 2006. He now leads the Tropical and Emerging Infectious Diseases team within the Global and Tropical Health Division. He is Professor in Medicine at the Northern Territory Medical Program, Flinders University, Adjunct Professorial Fellow at Charles Darwin University and Adjunct Professor at James Cook University. He works as a senior staff specialist physician at Royal Darwin Hospital, where he was Director of Infectious Diseases until 2019.

Other researchers and personnel

Professor Malcolm McDonald, Professor Julianne Coffin, Professor Andrew Steer, Raymond Christophers, Dr Hannah Thomas, Dr Tracy McRae, Stephanie Enkel, Marianne Mullane, Associate Professor Roz Walker, Dr Julie Marsh, Professor Luchiana Romani and Vicky O’Donnell OAM.

Partners

This case study was developed with input from Professor Asha Bowen and in partnership with The Kids Research Institute.

References

The information and images from which impact case studies are produced may be obtained from a number of sources including our case study partner, NHMRC’s internal records and publicly available materials. Key sources of information consulted for this case study include:

1 Currie BJ, Carapetis JR: Skin infections and infestations in Aboriginal communities in northern Australia. Australas J Dermatol 2000, 41(3):139–143

2 Yeoh DK, Anderson A, Cleland G, Bowen AC. Are scabies and impetigo “normalised”? A cross-sectional comparative study of hospitalised children in northern Australia assessing clinical recognition and treatment of skin infections. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2017 Jul 3;11(7)

3Andrews R and Kearns T. 2009, East Arnhem Regional Healthy Skin Project: Final Report 2008, Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, Darwin.

4 Enkel SL, Clements C, Thomas HM, McRae T, Amgarth-Duff I, Mullane M, Wiese L, Bedford L, Lansbury N, Carapetis JR, Bowen AC. “You can't heal yourself in that setting and you wouldn't expect other people in this country to”: Yarning about housing and environmental health in remote Aboriginal communities of Western Australia. Health & Place. 2025 Nov 1;96

5Gramp P, Gramp D. Scabies in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations in Australia: A narrative review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2021 Sep 30;15(9)

6Bowen AC, Mahe A, Hay RJ, Andrews RM, Steer AC, Tong SY, Carapetis JR. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PloS one. 2015 Aug 28;10(8)

7Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2009. A picture of Australia’s children 2009. Cat. no. PHE 112. Canberra: AIHW

8Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2024. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: summary report August 2024. AIHW: Australian Government. Accessed 22 May 2025.